Mononuclear U(IV) complexes and ningyoite as major uranium species in lake sediments

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as- Share this article

Article views:13,430Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

Abstract

Figures and Tables

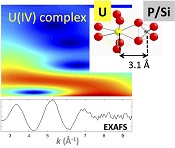

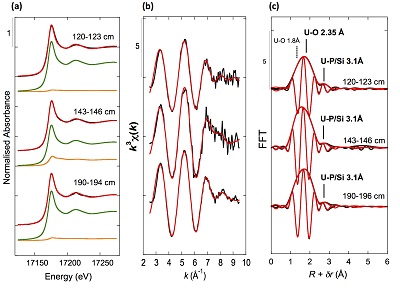

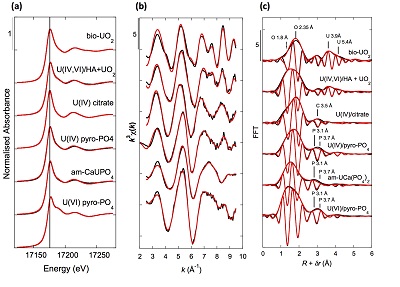

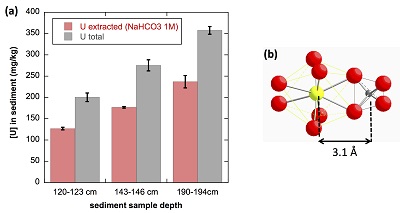

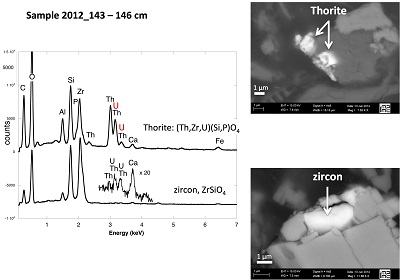

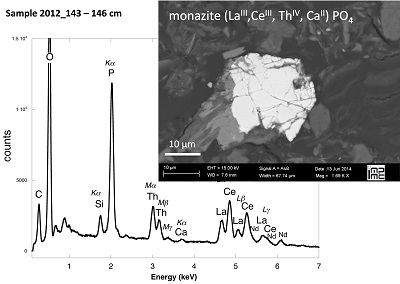

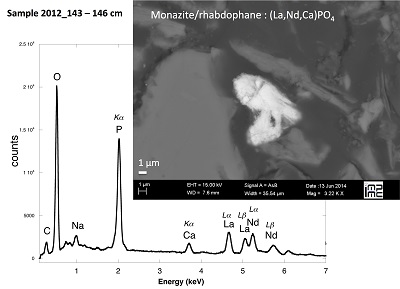

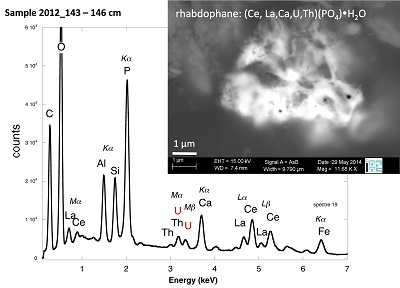

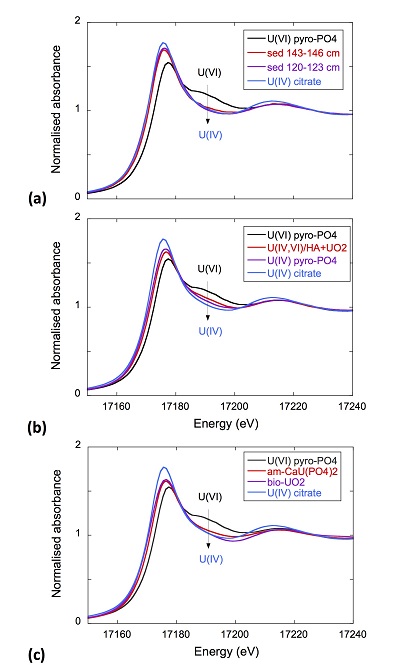

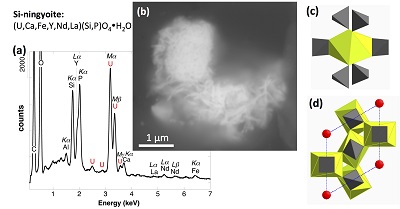

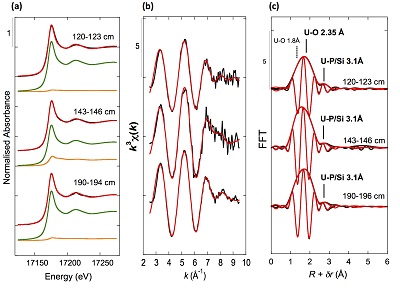

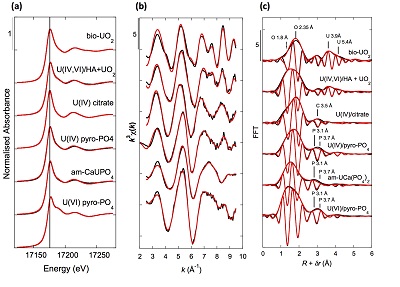

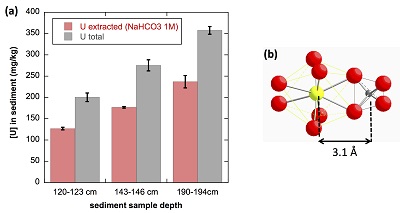

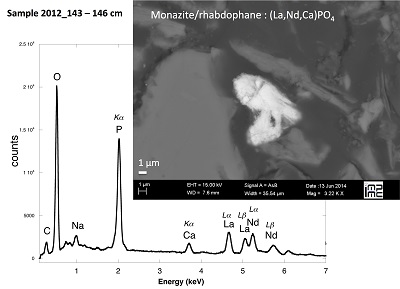

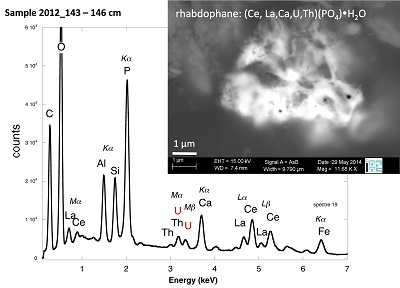

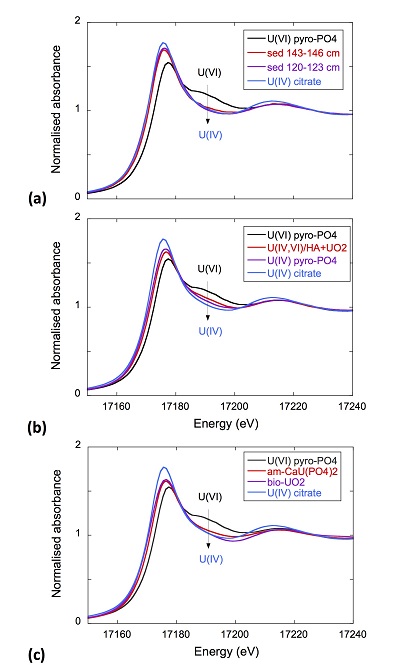

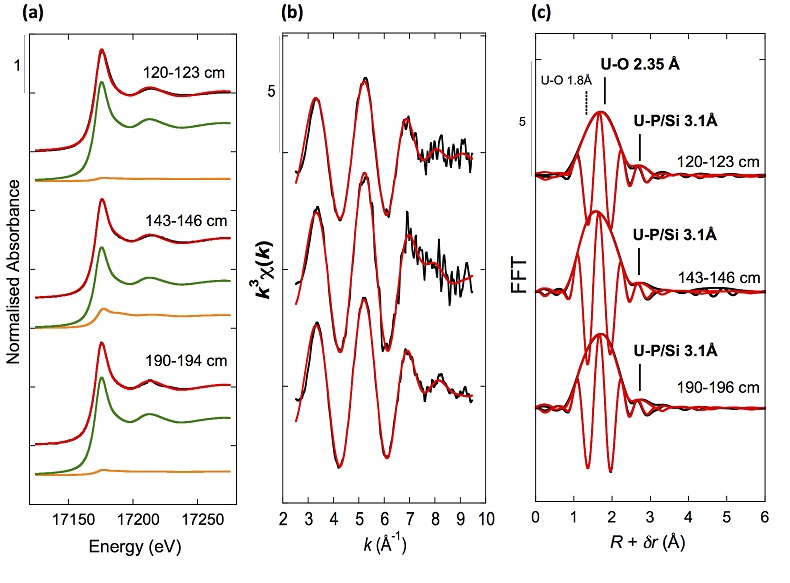

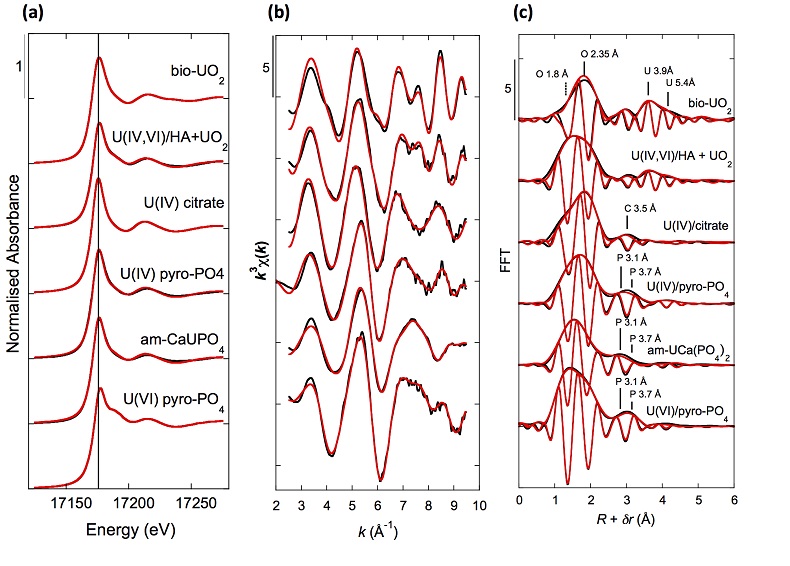

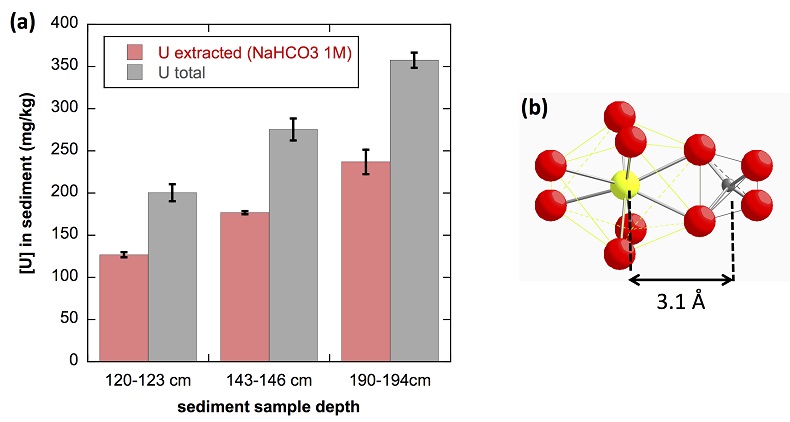

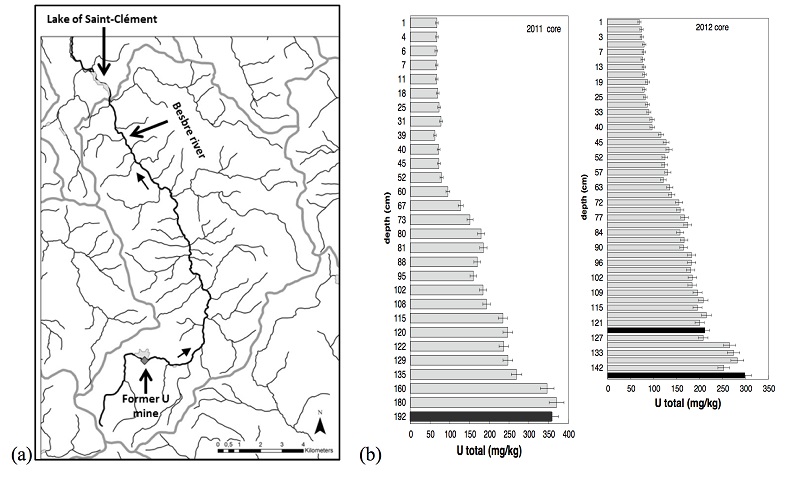

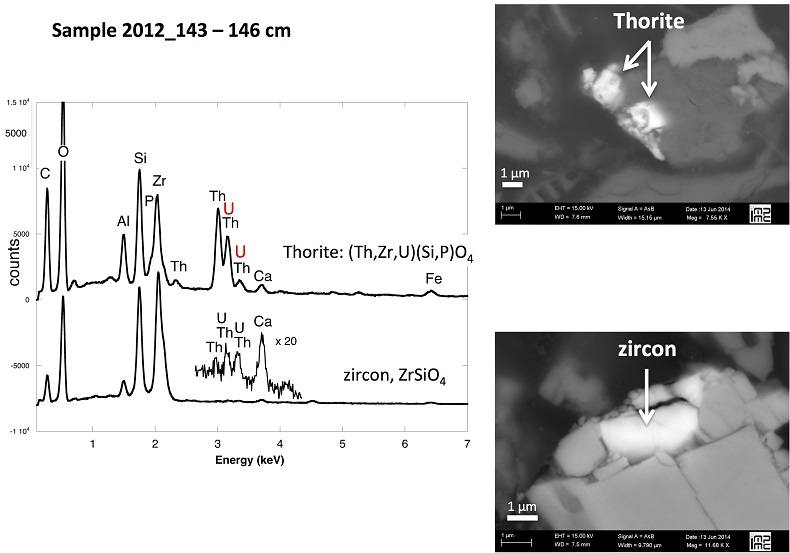

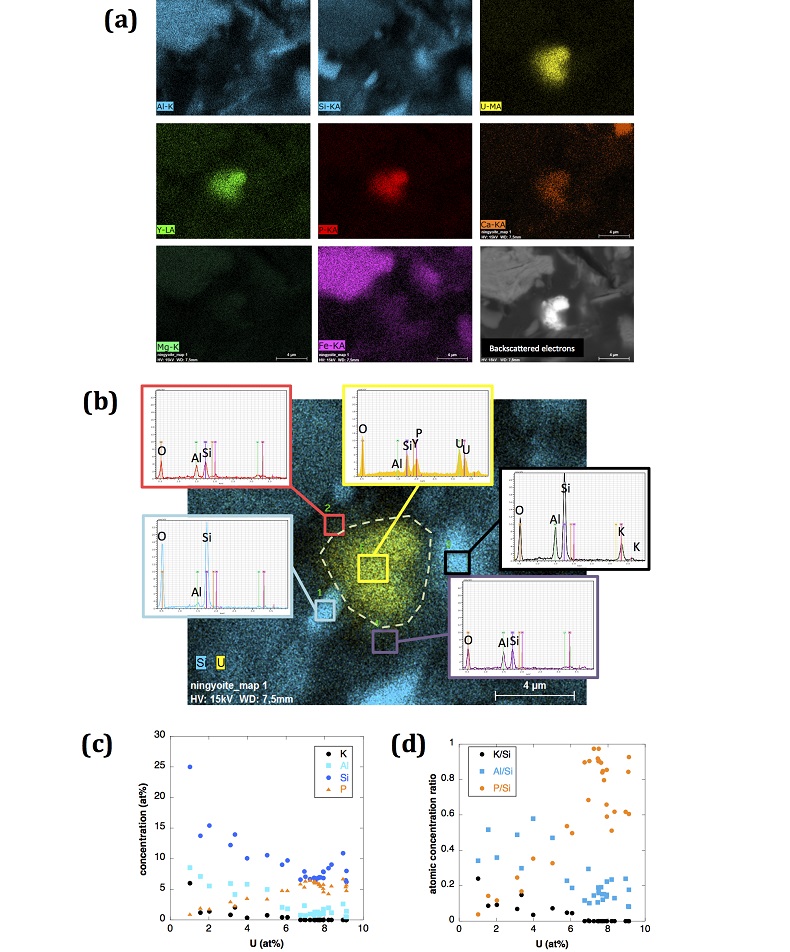

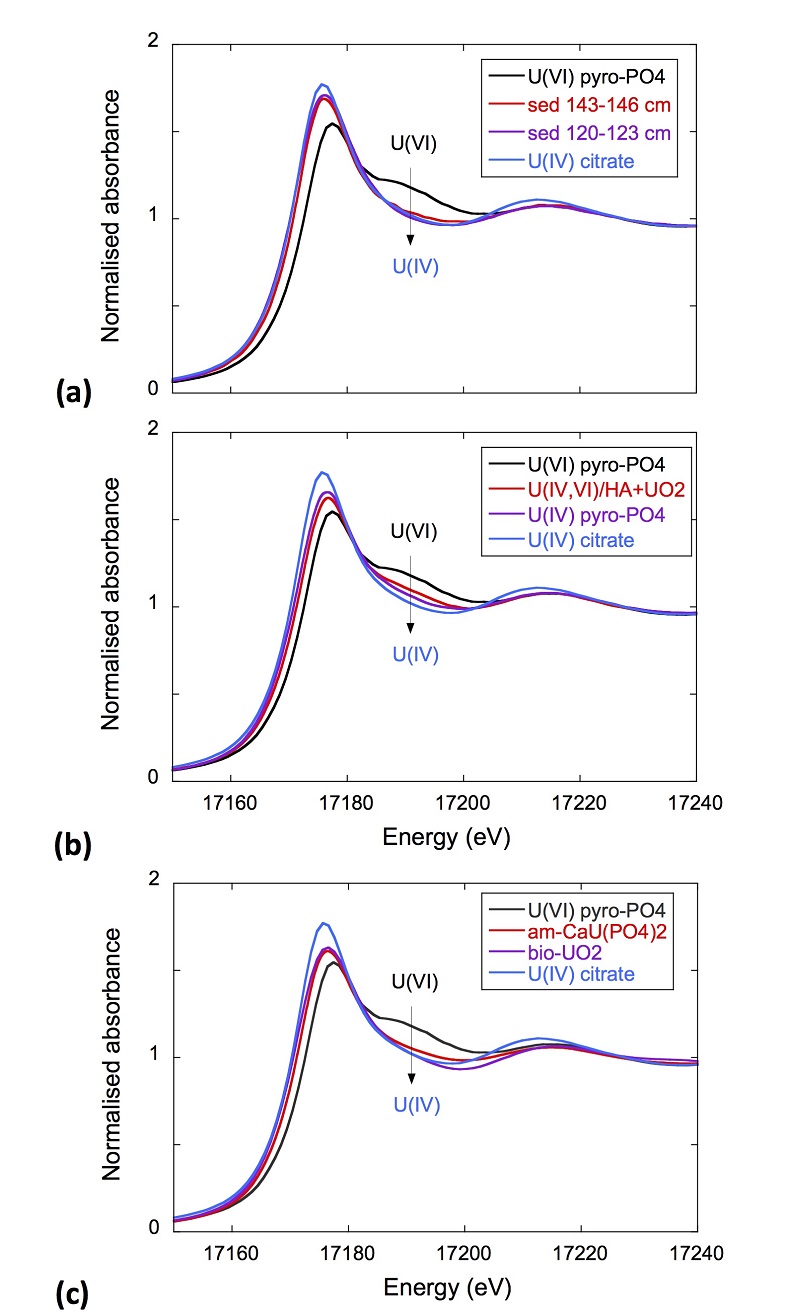

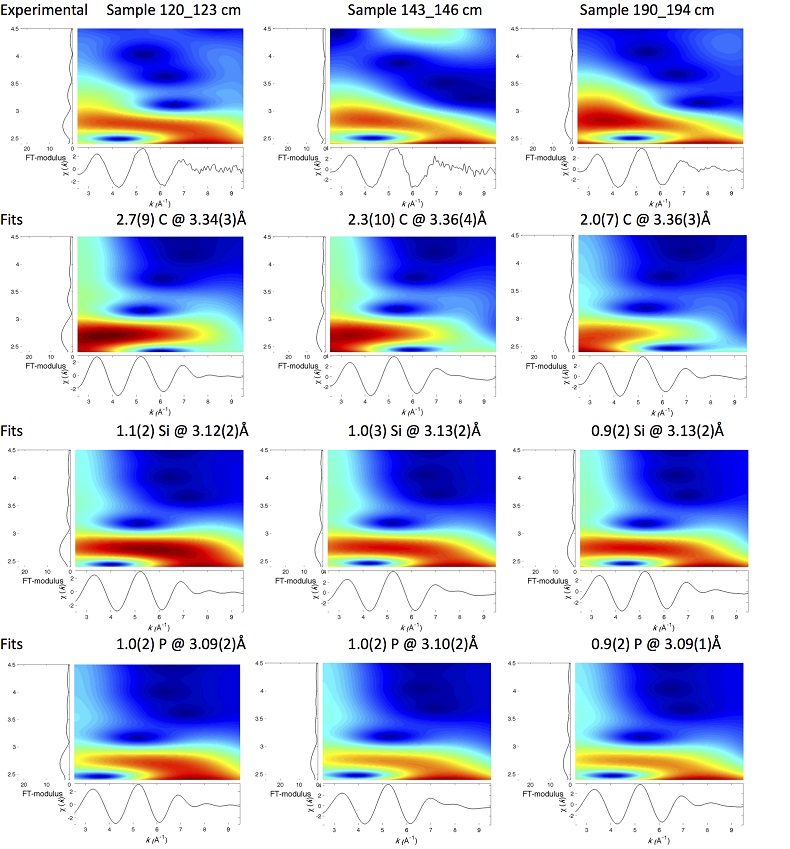

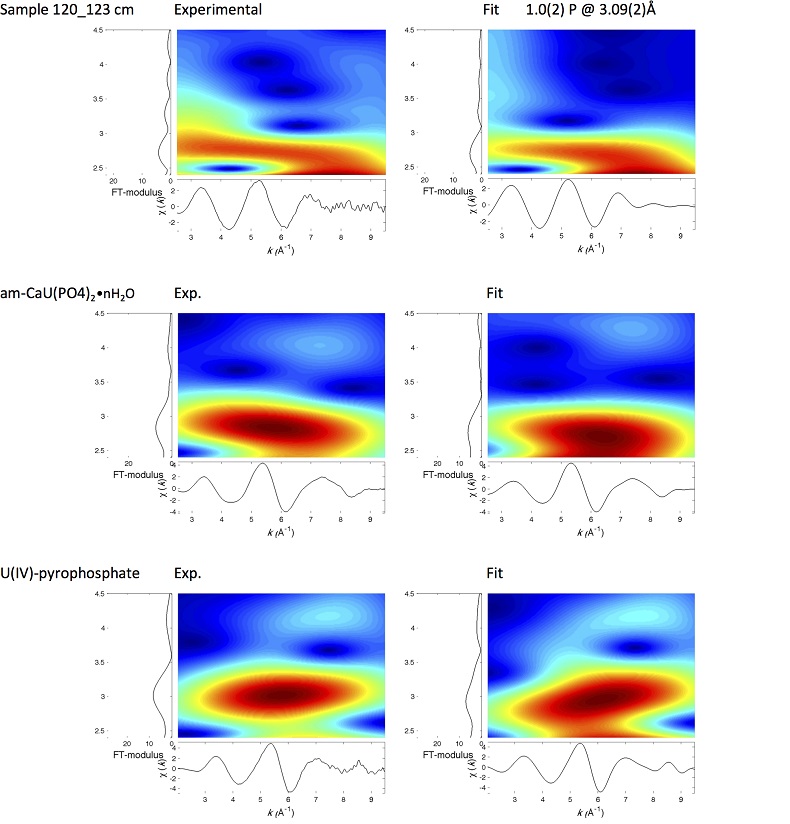

Figure 1 (a) EDXS analysis (Table S-2) and (b) Backscattered electron SEM image of Si-ningyoite in sample 143-146 cm with nano-sized acicular shaped crystals characteristic of the ningyoite and rhabdophane group minerals. Coordination of the (c) UIVO8 polyhedron (yellow) to phosphate tetrahedra (gray), and (d) cation polyhedra in the ningyoite/rhabdophane structure (Table S-4). |  Figure 2 Uranium LIII-edge XANES and EXAFS data of the lake sediment samples (black). (a) Linear Combination Fits (red) of the XANES spectra included U(IV) citrate (green) and U(VI) pyrophosphate (orange) as components. (b) Shell-by-shell fits (red) of the unfiltered k3χ(k) EXAFS spectra and (c) their Fast Fourier Transforms are displayed. See Table S-3 for fitting parameters. |  Figure 3 Uranium LIII-edge XANES and EXAFS data of relevant model compounds (black). (a) Linear Combination Fits (red) of the XANES spectra, (b) shell-by-shell fitting of the unfiltered k3χ(k) functions and (c) their Fast Fourier Transforms are displayed (red). See Table S-3 for fitting parameters. |  Figure 4 (a) Concentration of U(IV) extracted by O2-free NaHCO3 (1M) solution compared to total bulk U. (b) Local structure of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate bidendate edge-sharing complexes determined by EXAFS analysis as major solid state species of uranium in the sediments studied (Fig. 2, Table S-3). The phosphate/silicate tetrahedron could be connected to either organic or inorganic substrates. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

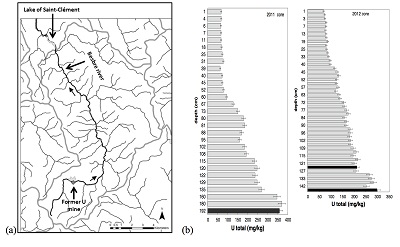

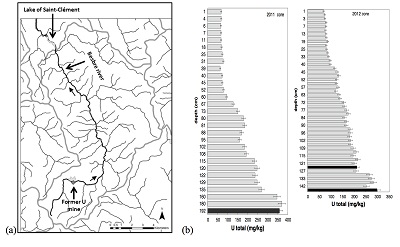

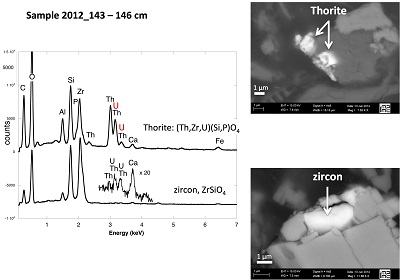

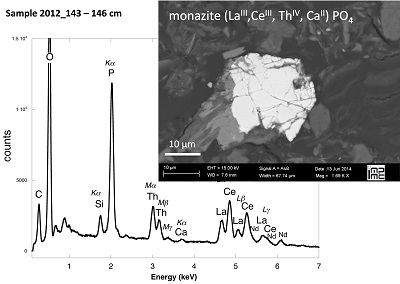

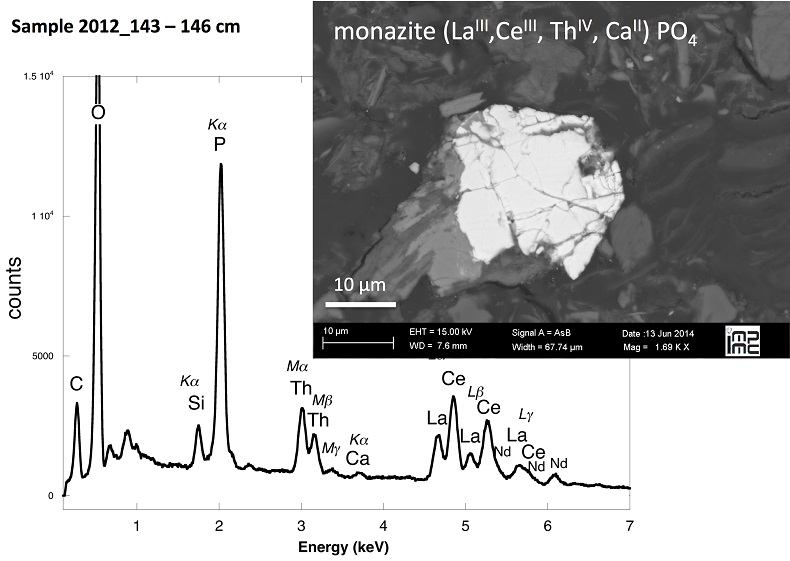

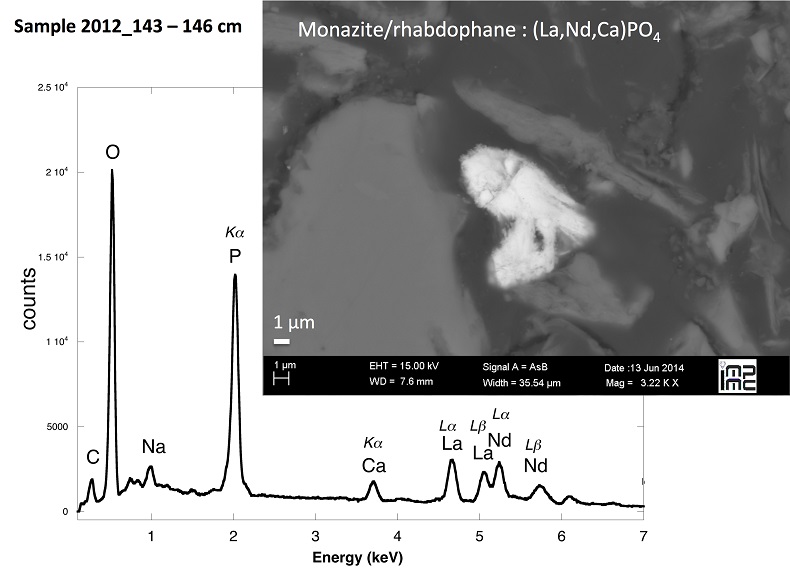

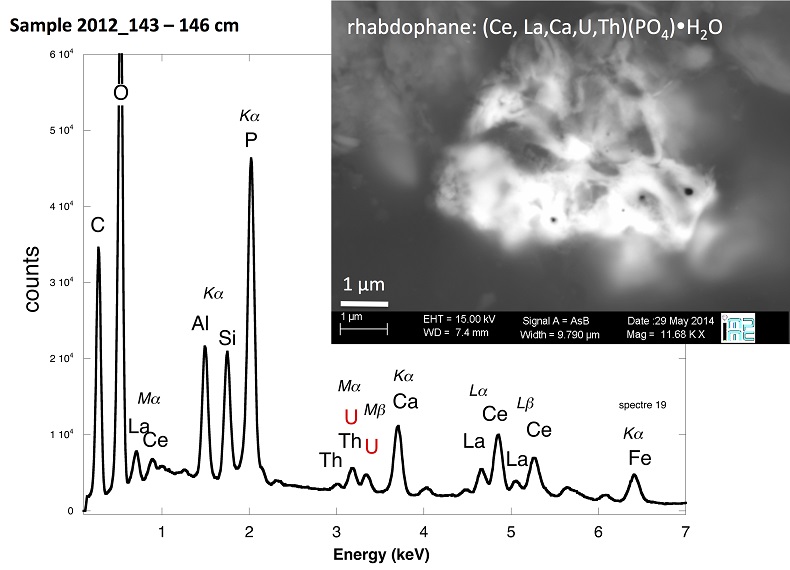

Table S-1 Chemical composition of the samples studied. The uncertainty on last digit is given in parenthesis. |  Table S-2 SEM-EDXS semi-quantitative analyses of U-bearing mineral phases identified in the 143-146 cm sediment sample. Data are expressed in percentage of oxides with ~15 % relative uncertainties estimated from standard deviations over 2 to 4 analyses. Characteristic molar ratios in mol/mol are given below. |  Table S-3 Results of XANES Linear Combination fit (LCF) and of EXAFS shell-by-shell fit for the Saint-Clément lake sediment (Fig. 2) and for relevant model compounds (Fig. 3). The XANES LCF components are aU(IV) citrate and bU(VI) pyrophosphate (Fig S-7). XANES LCF parameters are given in percentage of total uranium in the sample. EXAFS fitting parameters include R(Å): interatomic distances; N: number of neighbours; σ(Å): Debye Waller factor, ∆E0(eV): threshold energy shift in electron volts. For each parameter, the uncertainty on last digit is given in parenthesis. Rf and χ2R are Goodness of Fit parameters. For the sediment samples, the two χ2R values refer to fit solutions including P or Si as second neighbour, respectively. Detailed fitting procedure is reported in SI-6. |  Table S-4 Selected bond distances calculated from available crystal structure data for U(IV)-bearing phosphate and silicate minerals relevant to the present study. The U4+ ion is 8-fold coordinated to oxygen atoms at an average distance of <2.37 Å> in synthetic CaU(PO4)2, a xenotime-analogue of ningyoite, as well as in coffinite and uraninite (Wyckoff, 1963). The U-P distances at ~3.1 Å and at ~3.7 Å correspond to edge-sharing bidentate bridging, and corner-sharing monodentate bridging, respectively, of the UO8 group to a PO4 tetrahedron. Both U-P distances are expected in ningyoite that has a rhabdophane structure (Muto et al., 1959) (Fig. 1c). This UO8-PO4 bridging scheme is similar to the UO8-SiO4 bridging scheme in coffinite group minerals. In addition, in these various mineral structures, the MeO8 polyhedron shares edges with MeO8 polyedra within the 3.6-4.1Å distance range (Fig. 1d). None of these U-Me paths is observed in the EXAFS data of our sediment samples (Fig. 2, Table S-3). |  Figure S-1 (a) Sampling site location and (b) uranium content in the sediments studied. Bottom lake sediments were cored in Lake Saint-Clément located in Allier, Massif Central, France. The lake is supplied by the Besbre River that drains the discharges from the Bois-Noirs treated mine water, located 20 km upstream from the lake. The uranium ore body of Bois Noirs is a hydrothermal vein deposit hosted by a Hercynian granite. The major mineralisation consists of pitchblende/uraninite [UO2+x] partly replaced by coffinite [USiO4], deposited with minor pyrite and marcasite [FeS2] in massive quartz [SiO2] veins (Cuney, 1978). Supergene weathering formed secondary uranyl minerals, mostly torbernite [Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2•8-12(H2O)], uranophane [Ca(UO2)2SiO3(OH)2•5(H2O)] and uranopilite [(UO2)6(SO4)O2(OH)6(H2O)6]•8(H2O)]. Granitic accessory minerals as zircon [ZrSiO4], thorite [ThSiO4] and monazite [REEPO4] are considered as the primary uranium source for the hydrothermal deposit. About 7000 t of U were extracted between 1958 and 1980 and about 1.3 Mt of fine mill tailings are stored in a pond closed by a dam, from which percolating waters are treated (IRSN, 2015). The U content in the bottom lake sediments of Lake Saint-Clément increases regularly with depth down to about 1.5 to 2 metres depth. In order to facilitate the determination of uranium speciation in the present study, we focused on three concentrated deep sediment samples indicated in black colour in (b). Chemical analysis procedures are reported in Supplementary Information §1 and complete analysis of the three samples studied is reported in Table S-1. |  Figure S-2 Backscattered electrons SEM image and SEM-EDXS analyses of uranium–rich P-thorite (auerlite) and zircon crystals in the sediment sample 2012_143-146cm. Corresponding semi-quantitative analyses are reported in Table S-1. |  Figure S-3 Backscattered electrons SEM image and SEM-EDXS analysis of Th-monazite in the 2012_143-146cm sediment samples. Corresponding semi-quantitative analyses are reported in Table S-2. |

| Table S-1 | Table S-2 | Table S-3 | Table S-4 | Figure S-1 | Figure S-2 | Figure S-3 |

Figure S-4 Backscattered electrons SEM image and SEM-EDXS analysis of monazite grain coated by aggregates of rhabdophane crystals with characteristic acicular shape, in the 2012_143-146cm sediment sample. Corresponding semi-quantitative analysis are reported in Table S-2. |  Figure S-5 Backscattered electrons SEM image and SEM-EDXS analysis of U-rich rhabdophane aggregate, in the 2012_143-146 cm sediment sample. Corresponding semi-quantitative analysis are reported in Table S-2. |  Figure S-6 (a) Additional SEM-EDXS data for the area surrounding the Si-ningyoite grain shown in Figure 1, including: elemental maps obtained from integrated intensity of specific emission lines. (b) Spectra of specific areas in and around the Si-ningyoite grain. (c) Elemental compositions obtained from 25 punctual analyses within the dashed area given in atomic concentrations. (d) Atomic concentration ratios. These data indicate that the composition of the Si-ningyoite grain can be isolated from that of surrounding K-feldspar, quartz and clays particles, which exhibit different Al/Si, and K/Si ratios. This result is consistent with the classical ~1 µm3 interaction volume of a SEM probe, especially in a heavy material as a U-phosphate mineral. Semi-quantitative analysis obtained from four EDX spectra with high counting rate (0.5 – 1 million counts) is given in Table S-2. |  Figure S-7 U LIII-edge XANES spectra for the U(IV) and U(VI) model compounds, namely U(IV) citrate and U(VI) pyrophosphate, compared to (a) two of the studied sediment samples, (b) the U(IV) pyrophosphate and the U(IV)/HA+UO2 model compounds, and (c) the biogenic UO2 and the amorphous CaU(PO4)2•nH2O model compounds. Among our model compounds spectra, U(IV)-citrate and U(VI)-pyrophosphate were chosen as fitting components since they exhibited the purest U(IV) and U(VI) compositions, as compared to our other model compounds (Table S-3). |  Figure S-8 Continuous Cauchy-Wavelet transform (CCWT) of U LIII-edge EXAFS data for the three lake sediment samples studied (from left to right) compared to CCWT of shell-by-shell fits with C, Si or P atoms as second neighbours (from top to bottom). The fits with ~2.5 U-C paths reasonably matched the experimental k3-EXAFS and FT but yielded χ2R ~20 % larger than the U-P or U-Si fits reported in Table S-3 and Figure 3. Moreover, the strong CCWT signal at k < 5 Å-1 arising from the C atoms poorly matched the CCWT of the experimental data compared to the CCWT of the P or Si fits. However, potential bonding of U(IV) to carboxylic/phenolic or carbonate groups, in addition to phosphate/silicate groups, cannot be excluded, since CCWT of the experimental data suggests a minor contribution of C atoms at k < 5 Å-1, especially for sample 190-194 cm. Uncertainties on the fit parameters are given in parentheses and refer to the last digit (Table S-3, Fig. 3). The colour code corresponds to the EXAFS signal intensity in arbitrary units, increasing from blue to red. The ordinate axis corresponds to the distance R+∆r (Å) from the U absorbing atom, uncorrected from phase-shift. The CCWT analysis was limited to the 2.4-4.5 Å R+∆r-range, in order to avoid the high intensity EXAFS signal from the first neighbour oxygen atoms around the U absorbing atom. |  Figure S-9 Continuous Cauchy-Wavelet transform (CCWT) of U LIII-edge EXAFS data for the 120-123 cm depth lake sediment samples compared to the data for amorphous U(IV)-phosphate inorganic model compounds. CCWT of both data (left) and fits (right) show that, compared to a single P/Si second neighbour atom observed at R ~3.1 Å in the sediment samples, the contributions from U-P paths at R ~3.1 and 3.7 Å, centred at k ~5.5 Å-1 is sharp for the amorphous model compounds, as also indicated by the fitting results (Table S-3, Fig. 3). An additional U-U path at R ~4.1-4.3 Å, centered at k ~8 Å-1, is observed for U(IV)-pyrophosphate, and, to a lesser extent, for am-CaU(PO4)2•nH2O, whereas this contribution is absent for the sediment samples. Corresponding fitting parameters are reported in Table S-3. The CCWT analysis was limited to the 2.4-4.5 Å R+∆r-range, uncorrected for phase shift, in order to avoid the high intensity EXAFS signal from the first neighbour oxygen atoms around the U absorbing atom. |

| Figure S-4 | Figure S-5 | Figure S-6 | Figure S-7 | Figure S-8 | Figure S-9 |

top

Introduction

Redox cycling of uranium exerts a major control on its mobility in the environment because of the low solubility of U(IV) phases compared to that of U(VI) ones (Bargar et al., 2008

Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R., Giammar, D.E., Tebo, B.M. (2008) Biogenic uraninite nanoparticles and their importance for uranium remediation. Elements 4, 407-412.

). In natural anoxic environments such as estuarine and coastal sediments, early diagenesis conditions favour the reduction of uranyl species into low solubility U(IV) species, which decreases uranium concentrations in overlying waters and sediment pore-waters (Barnes and Cochran, 1993Barnes, C.E., Cochran, J.K. (1993) Uranium geochemistry in estuarine sediments: controls on removal and release processes. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 57, 555-589.

). Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007Wu, W.M., Carley, J., Luo, J., Ginder-Vogel, M.A., Cardenas, E., Leigh, M.B., Hwang, C.C., Kelly, S.D., Ruan, C.M., Wu, L.Y., Van Nostrand, J., Gentry, T., Lowe, K., Mehlhorn, T., Carroll, S., Luo, W.S., Fields, M.W., Gu, B.H., Watson, D., Kemner, K.M., Marsh, T., Tiedje, J., Zhou, J.Z., Fendorf, S., Kitanidis, P.K., Jardine, P.M., Criddle, C.S. (2007) In situ bioreduction of uranium(VI) to submicromolar levels and reoxidation by dissolved oxygen. Environmental Science and Technology 41, 5716-5723.

; Yabusaki et al., 2007Yabusaki, S.B., Fang, Y., Long, P.E., Resch, C.T., Peacock, A.D., Komlos, J., Jaffe, P.R., Morrison, S.J., Dayvault, R.D., White, D.C., Anderson, R.T. (2007) Uranium removal from groundwater via in situ biostimulation: field-scale modeling of transport and biological processes. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 93, 216-235.

) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005Suzuki, Y., Kelly, S.D., Kemner, K.A., Banfield, J.F. (2005) Microbial populations stimulated for hexavalent uranium reduction in uranium mine sediment. Applied Environmental Microbiology 69, 1337-1346.

; Bargar et al., 2008Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R., Giammar, D.E., Tebo, B.M. (2008) Biogenic uraninite nanoparticles and their importance for uranium remediation. Elements 4, 407-412.

) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008Kelly, S.D, Kemner, K.M., Carley, J., Criddle, C., Jardine, P.M., Marsh, T.L., Phillips, D., Watson, D., Wu, W.M. (2008) Speciation of uranium in sediments before and after in situ biostimulation. Environmental Science and Technology 42, 1558-1564.

; Alessi et al., 2014aAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Janot, N., Suvorova, E.I., Cerrato, J.M., Giammar, D.E., Davis, J.E., Fox, P.M., Williams, K.H., Long, P.E., Handley, K.M., Bernier-Latmani, R., Bargar, J.R. (2014a) Speciation and Reactivity of Uranium Products Formed during in Situ Bioremediation in a Shallow Alluvial Aquifer. Environmental Science and Technology 48, 12842-12850.

; Bargar et al., 2013Bargar, J.R., Williams, K.H., Campbell, K.M., Long, P.E., Stubbs, J.E., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Alessi, D.S., Stylo, M., Webb, S.M., Davis, J.A., Giammar, D.E., Blue, L.Y., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2013) Uranium redox transition pathways in acetate-amended sediments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 110, 4506-4511.

; Newsome et al., 2014Newsome, L., Morris, K., Lloyd, J.R. (2014) The biogeochemistry and bioremediation of uranium and other priority radionuclides. Chemical Geology 363, 164-184.

). Ex situ incubations of aquifer sediments under anoxic conditions have highlighted the importance of non-crystalline U(IV) species as major products of microbial reduction of uranyl (Sharp et al., 2011Sharp, J.O., Lezama-Pcheco, J.S., Schofield, E.J., Junier, P., Ulrich, K-U., Chinni, S., Veeramani, H., Margot-Roquier, C., Webb, S.M., Tebo, B.M., Giammar, D.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) et Uranium speciation and stability after reductive immobilization in aquifer sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 6497-6510.

; Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). In laboratory bioassays, mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate complexes, in which a U(IV) ion coordinates to a PO4 group, have been especially observed as products of microbial uranyl reduction (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Fletcher et al., 2010Fletcher, K.E., Boyanov, M.I., Thomas, S.H., Wu, Q., Kemner, K.M., Löffler, F.E. (2010) U(VI) reduction to mononuclear U(IV) by Desulfitobacterium species. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 4705-4709.

; Sivaswamy et al., 2011Sivaswamy, V., Boyanov, M.I., Peyton, B.M., Viamajala, S., Gerlach, R., Apel, W.A., Sani, R.K., Dohnalkova, A., Kemner, K.M., Borch, T. (2011) Multiple Mechanisms of Uranium Immobilization by Cellulomonas sp. Strain ES6. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 108, 264-276.

). U(IV)-phosphate mineral phases as ningyoite CaU(PO4)2•2H2O have also been identified after microbial reduction of dissolved uranyl in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Lee et al., 2010Lee, S.Y., Baik M.H., Choi, J.W. (2010) Biogenic formation and growth of uraninite (UO2). Environmental Science and Technology 44, 8409-8414.

) or after reduction of uranyl phosphate mineral phases (Khijniak et al., 2005Khijniak, T.V., Slobodkin, A.I., Coker, V., Renshaw, J.C., Livens, F.R., Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A., Birkeland, N.K., Medvedeva-Lyalikova, N.N., Lloyd, J.R. (2005) Reduction of Uranium(VI) Phosphate during Growth of the Thermophilic Bacterium Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 6423-6426.

; Rui et al., 2013Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

). The occurrence and distribution of non-uraninite U(IV) phases in natural systems is however scarcely documented (Qafoku et al., 2009Qafoku, N.P., Nikolla, P., Kukkadapu, R.K., Ravi, K., Mckinley, J.P., James, P., Arey, B.W., Kelly, S.D., Wang, C.M., Resch, C.T., Long, P.E. (2009) Uranium in framboidal pyrite from a naturally bioreduced alluvial sediment. Environmental Science and Technology 43, 8528-8534.

). Recently, Campbell et al. (2012)Campbell, K.M., Kukkadapu, R.K., Qafoku, N.P., Peacock, A.D., Lesher, E., Williams, K.H., Bargar, J.R., Wilkins, M.J., Figueroa, L., Ranville, J., Davis, J.A., Long, P.E. (2012) Geochemical, mineralogical and microbiological characteristics of sediment from a naturally reduced zone in a uranium-contaminated aquifer. Applied Geochemistry 27, 1499-1511.

showed that non-crystalline mononuclear U(IV) is present in aquifer sediments at the Rifle site. On the basis of this observation, it can be suspected that non-crystalline U(IV) species may form in other reducing environments, among which lacustrine sediments have a global environmental significance since they represent major uranium accumulation reservoirs in freshwater watersheds. Studies of uranium distribution in lacustrine environments suggested associations of U with organic matter in bottom lake sediments (Ueda et al., 2000Ueda, S., Hasegawa, H., Iyogi, T., Kawabata, H., Kondo, K. (2000) Investigation of physicochemical form of uranium in sediment of brackish Lake Obushi using sequential extraction procedure. Limnology 13, 231-236.

; Chappaz et al., 2010Chappaz, A., Gobeil, C., Tessier, A. (2010) Controls on uranium distribution in lake sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 74, 203-214.

) as well as in the water column (Alberic et al., 2000Alberic, P., Viollier, E., Jezequel, D., Grosbois, C., Michard, G. (2000) Interactions between trace elements and dissolved organic matter in the stagnant anoxic deep layer of a meromictic lake. Limnology and Oceanography 45, 1088-1096.

) but no direct determinations of uranium speciation in such environments have been yet reported.Here we used a combination of X-ray absorption spectroscopy, electron microscopy and selective chemical extraction to investigate uranium speciation in contaminated lake sediments. We show that uranium occurs mainly in the form of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate complexes, and to a lesser extent as nano-crystalline U(IV)-phosphate of the ningyoite-rhabdophane group. This result has major implications for better predicting the behaviour and fate of uranium in lacustrine environments.

top

Sampling Site and Analytical Methods

Sediment cores were sampled in March 2011 and October 2012, with an Uwitec© gravity corer, in the lake Saint-Clément, in a high U geological background area located ~20 kilometers downstream from the former uranium mine of Bois Noirs/Limouzat in the Massif Central, France (Fig. S-1). Core sections were immediately placed in a glove bag, purged with N2, sealed in hermetic containers, transported below 4 °C, and dried under vacuum in a glove-box at the IMPMC laboratory 24 hours after sampling. Samples were preserved under anoxic conditions until and during mineralogical and spectroscopic analyses, and during chemical extractions. For SEM-EDXS analyses, sediments were embedded in epoxy resin and prepared as thin sections. Here, we studied the most concentrated samples collected at 120-123 cm and 143-146 cm depth in the 2012 core and at 190-194 cm depth in the 2011 core, with total bulk U contents of ~200, 275 and 360 mg/kg (Fig. S-1; Table S-1). To determine uranium solid-state speciation, we used X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) spectroscopy, Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy at the U LIII-edge, and Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDXS) analyses. In addition, we used 1M NaHCO3 O2-free solution extraction (Alessi et al., 2012

Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

) for evaluating the proportion of non-crystalline U(IV) species in the same samples. See Supplementary Information for detailed procedures.top

Identification of U-bearing Minerals in the Sediment Samples

X-ray diffraction indicated that the sediments consisted mainly of quartz, feldspar, micas and chlorite, in agreement with their chemical composition (Table S-1) and with the granitic geological substratum (Fig. S-1). The high organic carbon content ~12 wt % was related to fresh organic matter including vegetal debris. Barite [BaSO4] was detected under SEM-EDXS analyses, and pyrite [FeS2] was present as rare submicron sized crystals. Systematic SEM observations and EDXS analyses of the 143-146 cm sample revealed scarce U-bearing minerals (Table S-2): zircon, thorite (Fig. S-2), monazite (Fig. S-3), rhabdophane (Figs. S-4, S-5), and a nano-crystalline U-rich phosphate mineral of the ningyoite group (Figs. 1, S-6). Ningyoite was the most concentrated U phase identified in the sample, with the following approximate structural formula: [(U0.95Ca0.3Fe0.15Al0.15Y0.4Nd0.05)(PO4)(SiO4)•nH2O] (Table S-2, Fig. S-6). According to Muto et al. (1959)

Muto, T., Meyrowitz, R., Pommer, A., Murano, T. (1959) Ningyoite, a new uranous phosphate mineral from Japan. American Mineralogist 44, 633-650.

, powder XRD data of ningyoite [CaU(PO4)2•2H2O] indicate that this mineral is isostructural to rhabdophane [REE3+PO4•H2O], with an equivalent amount of U4+ and Ca2+ ions substituting for the REE3+ ions. In the mineral phase identified here, the excess of U4+ over Ca2+ is likely compensated by SiO44- for PO43- substitution, as in Si-rich ningyoite (Doinikova et al., 2014Doinikova, O.A., Sidorenko, G.A., Sivtsov, A.V. (2014) Phosphosilicates of tetravalent uranium. Doklady Earth Sciences 456, 755–758.

). Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007Doinikova, O.A. (2007) Uranium Deposits with a new phosphates types of blacks. Geology of Ore Deposits 49, 80-86.

) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005Khijniak, T.V., Slobodkin, A.I., Coker, V., Renshaw, J.C., Livens, F.R., Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A., Birkeland, N.K., Medvedeva-Lyalikova, N.N., Lloyd, J.R. (2005) Reduction of Uranium(VI) Phosphate during Growth of the Thermophilic Bacterium Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 6423-6426.

; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Lee et al., 2010Lee, S.Y., Baik M.H., Choi, J.W. (2010) Biogenic formation and growth of uraninite (UO2). Environmental Science and Technology 44, 8409-8414.

; Rui et al., 2013Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

). In the sediments studied here, evaluating the importance of the U(IV) mineral phases with respect to other uranium species required both bulk XANES and EXAFS analyses and selective chemical extractions assays.

Figure 1 (a) EDXS analysis (Table S-2) and (b) Backscattered electron SEM image of Si-ningyoite in sample 143-146 cm with nano-sized acicular shaped crystals characteristic of the ningyoite and rhabdophane group minerals. Coordination of the (c) UIVO8 polyhedron (yellow) to phosphate tetrahedra (gray), and (d) cation polyhedra in the ningyoite/rhabdophane structure (Table S-4).

top

Uranium Oxidation State

XANES analyses at the U LIII-edge indicated that uranium was mainly present as U(IV) in the sediment samples studied (Fig. 2a). Indeed, the shoulder at ~17190 eV that is characteristic of the uranyl ion, e.g., in U(VI)-pyrophosphate (Figs. 3a, S-7), was not observed in the XANES spectra of the sediment samples (Figs. 2a, S-7a). Linear Combination Fitting (LCF) of the XANES spectra indicated that the proportion of U(VI) accounted at most for 20 % of total U in the 143-146 cm sample and was below 10 % of total U in the two other sediment samples (Fig. 2a, Table S-3).

Figure 2 Uranium LIII-edge XANES and EXAFS data of the lake sediment samples (black). (a) Linear Combination Fits (red) of the XANES spectra included U(IV) citrate (green) and U(VI) pyrophosphate (orange) as components. (b) Shell-by-shell fits (red) of the unfiltered k3χ(k) EXAFS spectra and (c) their Fast Fourier Transforms are displayed. See Table S-3 for fitting parameters.

Figure 3 Uranium LIII-edge XANES and EXAFS data of relevant model compounds (black). (a) Linear Combination Fits (red) of the XANES spectra, (b) shell-by-shell fitting of the unfiltered k3χ(k) functions and (c) their Fast Fourier Transforms are displayed (red). See Table S-3 for fitting parameters.

top

Chemical Extraction as a Probe for Mononuclear U(IV) Species

The proportion of mononuclear U(IV) species in the sediment samples was evaluated by selective chemical extraction using a 1 M NaHCO3 O2-free solution under anoxic conditions using the protocol of Alessi et al. (2012)

Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

(Supplementary Information). As shown in Figure 4a, 65 ± 5 % of the total uranium content was extracted from the three samples by this method, and could be assigned to mononuclear U(IV). Indeed, non-crystalline U(IV) species may include mononuclear and polymerised U(IV)-complexes, the latter being less extractable than the former (Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). U(IV) bearing minerals identified by SEM-EDXS, including ningyoite, rhabdophane, thorite and zircon, thus likely accounted at most for 35 ± 5 % of the total uranium in the sediment samples.

Figure 4 (a) Concentration of U(IV) extracted by O2-free NaHCO3 (1M) solution compared to total bulk U. (b) Local structure of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate bidendate edge-sharing complexes determined by EXAFS analysis as major solid state species of uranium in the sediments studied (Fig. 2, Table S-3). The phosphate/silicate tetrahedron could be connected to either organic or inorganic substrates.

top

EXAFS Evidence for Mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate Complexes as Major U Species

U LIII-edge EXAFS data of the three sediment samples were rather similar to each other (Fig. 2b, c), and significantly different from that of biogenic nano-uraninite (Fig. 3b,c). Indeed, best fits of the sediment sample data were obtained with 8-9 U-O scattering paths at ~2.35 Å and ~1 U-P or U-Si path at ~3.1 Å, with similar fit quality for a P or Si neighbour (Figs. 2c, S-8, Table S-3). The U-O paths were consistent with U4+ ions 8-fold coordinated to oxygen atoms (Table S-4). A minor U-O path at a distance of ~1.8 Å improved the fits, accounting for <5-20 % of uranyl ions identified by XANES analysis (Fig. 2a, Table S-3).

The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013

Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Lee et al., 2010Lee, S.Y., Baik M.H., Choi, J.W. (2010) Biogenic formation and growth of uraninite (UO2). Environmental Science and Technology 44, 8409-8414.

; Boyanov et al., 2011Boyanov, M.I., Fletcher, K.E., Kwon, M.J., Rui, X., O’Loughlin, E.J., Löffler, F.E., Kemner, K.M. (2011) Solution and microbial controls on the formation of reduced U(IV) phases. Environmental Science and Technology 45, 8336-8344.

) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011Veeramani, H., Alessi, D., Suvorova, E., Lezama-Pacheco, J., Stubbs, J., Dippon, U., Kappler, A., Bargar, J., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) Products of abiotic U(VI) reduction by biogenic magnetite and vivianite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 2512-2528.

) U(VI) reduction. Moreover, a sole P/Si atom was detected beyond the first oxygen coordination sphere of the U absorber, which contrasts with the higher number of second neighbours observed for amorphous U(IV) phases (Table S-3, Fig. S-9). This result demonstrated that uranium was mainly present as mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate complexes in the sediment, likely accounting for most of the extractable U(IV) fraction (65 ± 5 % of total U in Fig. 4).Neither the U-U paths of the uraninite structure (Fig. 3), nor the U-P/Si at 3.7-3.8 Å (Fig. 1c) and U-U/Th/Ca/REE paths at 3.6-4.1 Å (Fig. 1d) that are characteristic of crystalline (Table S-4) and amorphous (Fig. S-9) U(IV)–bearing phosphate and silicate mineral phases, were detected around the U absorber in the sediments (Fig. 2c, Table S-3). Owing to the sensitivity of EXAFS to minor components (Alessi et al., 2012

Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

), crystalline phases thus accounted for less than 10 % of U, suggesting that the non-extractable U fraction in the sediments (35 ± 5 % of total U in Fig. 4) consisted of nano-crystalline or amorphous U(IV) phases. For instance, biogenic nano-crystalline U(IV) is not easily extracted by 1M NaHCO3 (Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). We thus infer that a fraction of the primary U(IV)-bearing uranium minerals identified by SEM-EDXS, as zircon and thorite are likely metamict because of their high U and Th contents (Table S-2), which would make such phases difficult to detect by EXAFS as minor phases in a mixture with mononuclear U(IV) complexes. Accordingly, ~1 instead of 4 Pu-Zr paths at 3.6 Å were reported for Pu LIII-edge EXAFS analysis of highly metamict zircon (Begg et al., 2000Begg, B.D., Hess, N.J., Weber, W.J., Conradson, S.D., Schweiger, M.J., Ewing, R.C. (2000) XAS and XRD study of annealed 238Pu- and 239Pu-substituted zircons (Zr0.92Pu0.08SiO4). Journal of Nuclear Materials 278, 212-224.

). In the same way, ~ 2 to 4 times less P and U neighbours were observed by EXAFS in our amorphous U(IV) model compounds (Table S-3, Fig. 3) than in their crystalline analogues (Table S-4).Finally, Continuous Cauchy Wavelet Transform analysis of the EXAFS data confirmed that mononuclear U(IV) was mainly complexed to phosphate or silicate groups, even if a minor contribution from carboxylic/phenolic or carbonate groups could not be excluded (Fig. S-8). Hence, our EXAFS results indicated that uranium was mainly in the form of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate complexes in the sediments studied and thus provide a direct clue of the importance of such species in lacustrine systems.

top

Environmental Implications

The knowledge of uranium speciation in natural sediments impacted by anthropogenic activities is essential for predicting the fate of uranium during and after sediment deposition. In that context, lacustrine sediments are of particular importance because they represent important accumulation reservoirs for this element in continental watersheds. The present study yields evidence for mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate complexes as the main uranium species in lake sediments impacted by a former uranium mine. This observation reveals that uranium trapping mechanisms during early diagenesis of lacustrine sediments can virtually exclude uraninite formation, which has important implications for modelling uranium cycling in natural and contaminated freshwater systems. The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005

Khijniak, T.V., Slobodkin, A.I., Coker, V., Renshaw, J.C., Livens, F.R., Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A., Birkeland, N.K., Medvedeva-Lyalikova, N.N., Lloyd, J.R. (2005) Reduction of Uranium(VI) Phosphate during Growth of the Thermophilic Bacterium Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 6423-6426.

; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Lee et al., 2010Lee, S.Y., Baik M.H., Choi, J.W. (2010) Biogenic formation and growth of uraninite (UO2). Environmental Science and Technology 44, 8409-8414.

; Boyanov et al., 2011Boyanov, M.I., Fletcher, K.E., Kwon, M.J., Rui, X., O’Loughlin, E.J., Löffler, F.E., Kemner, K.M. (2011) Solution and microbial controls on the formation of reduced U(IV) phases. Environmental Science and Technology 45, 8336-8344.

; Rui et al., 2013Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems. Our results also indicate that U(IV)-phosphates such as ningyoite, although present, account for a minor fraction of the total U(IV). Such a phase could have formed in the sediment after bioreduction of either soluble U(VI) (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

) or, more likely, of a secondary U(VI)-phosphate/silicate mineral inherited from the uranium ore (Rui et al., 2013Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

) (Fig. S-1).Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010

Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

; Fletcher et al., 2010Fletcher, K.E., Boyanov, M.I., Thomas, S.H., Wu, Q., Kemner, K.M., Löffler, F.E. (2010) U(VI) reduction to mononuclear U(IV) by Desulfitobacterium species. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 4705-4709.

; Sivaswamy et al., 2011Sivaswamy, V., Boyanov, M.I., Peyton, B.M., Viamajala, S., Gerlach, R., Apel, W.A., Sani, R.K., Dohnalkova, A., Kemner, K.M., Borch, T. (2011) Multiple Mechanisms of Uranium Immobilization by Cellulomonas sp. Strain ES6. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 108, 264-276.

; Boyanov et al., 2011Boyanov, M.I., Fletcher, K.E., Kwon, M.J., Rui, X., O’Loughlin, E.J., Löffler, F.E., Kemner, K.M. (2011) Solution and microbial controls on the formation of reduced U(IV) phases. Environmental Science and Technology 45, 8336-8344.

; Veeramani et al., 2011Veeramani, H., Alessi, D., Suvorova, E., Lezama-Pacheco, J., Stubbs, J., Dippon, U., Kappler, A., Bargar, J., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) Products of abiotic U(VI) reduction by biogenic magnetite and vivianite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 2512-2528.

; Sharp et al., 2011Sharp, J.O., Lezama-Pcheco, J.S., Schofield, E.J., Junier, P., Ulrich, K-U., Chinni, S., Veeramani, H., Margot-Roquier, C., Webb, S.M., Tebo, B.M., Giammar, D.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) et Uranium speciation and stability after reductive immobilization in aquifer sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 6497-6510.

; Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). Such U(IV) mononuclear species could either be sorbed to the surface of phosphate (Veeramani et al., 2011Veeramani, H., Alessi, D., Suvorova, E., Lezama-Pacheco, J., Stubbs, J., Dippon, U., Kappler, A., Bargar, J., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) Products of abiotic U(VI) reduction by biogenic magnetite and vivianite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 2512-2528.

) as well as silicate minerals, or be bound to organic phosphoryl groups (Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). The major occurrence of such species in lacustrine sediments has important environmental implications since mononuclear U(IV) species are potentially more labile than uraninite (Cerrato et al., 2013Cerrato, J.M., Asner, M.N., Alessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Bernier-Latmani, R., Bargar, J.R., Giammar, D.E. (2013) Relative reactivity of biogenic and chemogenic uraninite and biogenic non crystalline U(IV). Environmental Science and Technology 47, 9756-9763.

; Alessi et al., 2014aAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Janot, N., Suvorova, E.I., Cerrato, J.M., Giammar, D.E., Davis, J.E., Fox, P.M., Williams, K.H., Long, P.E., Handley, K.M., Bernier-Latmani, R., Bargar, J.R. (2014a) Speciation and Reactivity of Uranium Products Formed during in Situ Bioremediation in a Shallow Alluvial Aquifer. Environmental Science and Technology 48, 12842-12850.

) and polymerised non-crystalline U(IV) phosphate phases (Alessi et al., 2014bAlessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

). Such lability raises issues concerning the long term fate of the mononuclear U(IV) species, especially when subjected to sharp redox changes, for example in sediment remediation strategies as dredging operations.top

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Evelyne Barker, Dr. Imène Esteve and Sebastien Charron, and Loic Martin and Ludovic Delbès, for their help in chemical, SEM, and XRD analyses, respectively. We also thank Prof. Jordi Bruno and another anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that have helped us to improve the quality of the manuscript. This study was supported by IRSN and CNRS-NEEDS Program. We thank EDF and DREAL Auvergne for having authorised access to the lake of Saint-Clément. The SEM equipment of IMPMC was funded by Région IDF, CNRS, UPMC and ANR. ESRF, French CRG and SSRL facilities are acknowledged for having provided beamtime. SSRL and SLAC are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515, the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER), and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). Partial support was provided by the U.S. DOE BER and SBR program.

Editor: Rodney C. Ewing

top

References

Alberic, P., Viollier, E., Jezequel, D., Grosbois, C., Michard, G. (2000) Interactions between trace elements and dissolved organic matter in the stagnant anoxic deep layer of a meromictic lake. Limnology and Oceanography 45, 1088-1096.

Show in context

Show in context Studies of uranium distribution in lacustrine environments suggested associations of U with organic matter in bottom lake sediments (Ueda et al., 2000; Chappaz et al., 2010) as well as in the water column (Alberic et al., 2000) but no direct determinations of uranium speciation in such environments have been yet reported.

View in article

Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

Show in context

Show in context To determine uranium solid-state speciation, we used X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) spectroscopy, Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy at the U LIII-edge, and Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDXS) analyses. In addition, we used 1M NaHCO3 O2-free solution extraction (Alessi et al., 2012) for evaluating the proportion of non-crystalline U(IV) species in the same samples.

View in article

The proportion of mononuclear U(IV) species in the sediment samples was evaluated by selective chemical extraction using a 1 M NaHCO3 O2-free solution under anoxic conditions using the protocol of Alessi et al. (2012) (Supplementary Information).

View in article

Owing to the sensitivity of EXAFS to minor components (Alessi et al., 2012), crystalline phases thus accounted for less than 10 % of U, suggesting that the non-extractable U fraction in the sediments (35 ± 5 % of total U in Fig. 4) consisted of nano-crystalline or amorphous U(IV) phases.

View in article

Alessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Janot, N., Suvorova, E.I., Cerrato, J.M., Giammar, D.E., Davis, J.E., Fox, P.M., Williams, K.H., Long, P.E., Handley, K.M., Bernier-Latmani, R., Bargar, J.R. (2014a) Speciation and Reactivity of Uranium Products Formed during in Situ Bioremediation in a Shallow Alluvial Aquifer. Environmental Science and Technology 48, 12842-12850.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

The major occurrence of such species in lacustrine sediments has important environmental implications since mononuclear U(IV) species are potentially more labile than uraninite (Cerrato et al., 2013; Alessi et al., 2014a) and polymerised non-crystalline U(IV) phosphate phases (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Alessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Janousch, M., Bargar, J.R., Persson, P., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2014b) The product of microbial uranium reduction includes multiple species with U(IV)-phosphate coordination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 131, 115–127.

Show in context

Show in context Ex situ incubations of aquifer sediments under anoxic conditions have highlighted the importance of non-crystalline U(IV) species as major products of microbial reduction of uranyl (Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Indeed, non-crystalline U(IV) species may include mononuclear and polymerised U(IV)-complexes, the latter being less extractable than the former (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

For instance, biogenic nano-crystalline U(IV) is not easily extracted by 1M NaHCO3 (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Such U(IV) mononuclear species could either be sorbed to the surface of phosphate (Veeramani et al., 2011) as well as silicate minerals, or be bound to organic phosphoryl groups (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

The major occurrence of such species in lacustrine sediments has important environmental implications since mononuclear U(IV) species are potentially more labile than uraninite (Cerrato et al., 2013; Alessi et al., 2014a) and polymerised non-crystalline U(IV) phosphate phases (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R., Giammar, D.E., Tebo, B.M. (2008) Biogenic uraninite nanoparticles and their importance for uranium remediation. Elements 4, 407-412.

Show in context

Show in context Redox cycling of uranium exerts a major control on its mobility in the environment because of the low solubility of U(IV) phases compared to that of U(VI) ones (Bargar et al., 2008).

View in article

Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Bargar, J.R., Williams, K.H., Campbell, K.M., Long, P.E., Stubbs, J.E., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Alessi, D.S., Stylo, M., Webb, S.M., Davis, J.A., Giammar, D.E., Blue, L.Y., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2013) Uranium redox transition pathways in acetate-amended sediments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 110, 4506-4511.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Barnes, C.E., Cochran, J.K. (1993) Uranium geochemistry in estuarine sediments: controls on removal and release processes. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 57, 555-589.

Show in context

Show in context In natural anoxic environments such as estuarine and coastal sediments, early diagenesis conditions favour the reduction of uranyl species into low solubility U(IV) species, which decreases uranium concentrations in overlying waters and sediment pore-waters (Barnes and Cochran, 1993).

View in article

Begg, B.D., Hess, N.J., Weber, W.J., Conradson, S.D., Schweiger, M.J., Ewing, R.C. (2000) XAS and XRD study of annealed 238Pu- and 239Pu-substituted zircons (Zr0.92Pu0.08SiO4). Journal of Nuclear Materials 278, 212-224.

Show in context

Show in contextAccordingly, ~1 instead of 4 Pu-Zr paths at 3.6 Å were reported for Pu LIII-edge EXAFS analysis of highly metamict zircon (Begg et al., 2000).

View in article

Bernier-Latmani, R., Veeramani, H., Dalla Vecchia, E., Junier, P., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Suvorova, E.I., Sharp, J.O., Wigginton, N.S., Bargar, J.R. (2010) Non-uraninite products of microbial U(VI) reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 9456-9462.

Show in context

Show in context In laboratory bioassays, mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate complexes, in which a U(IV) ion coordinates to a PO4 group, have been especially observed as products of microbial uranyl reduction (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011).

View in article

U(IV)-phosphate mineral phases as ningyoite CaU(PO4)2•2H2O have also been identified after microbial reduction of dissolved uranyl in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010) or after reduction of uranyl phosphate mineral phases (Khijniak et al., 2005; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011) U(VI) reduction.

View in article

The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems.

View in article

Such a phase could have formed in the sediment after bioreduction of either soluble U(VI) (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010) or, more likely, of a secondary U(VI)-phosphate/silicate mineral inherited from the uranium ore (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. S-1).

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Boyanov, M.I., Fletcher, K.E., Kwon, M.J., Rui, X., O’Loughlin, E.J., Löffler, F.E., Kemner, K.M. (2011) Solution and microbial controls on the formation of reduced U(IV) phases. Environmental Science and Technology 45, 8336-8344.

Show in context

Show in context Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011) U(VI) reduction.

View in article

The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems.

View in article

Campbell, K.M., Kukkadapu, R.K., Qafoku, N.P., Peacock, A.D., Lesher, E., Williams, K.H., Bargar, J.R., Wilkins, M.J., Figueroa, L., Ranville, J., Davis, J.A., Long, P.E. (2012) Geochemical, mineralogical and microbiological characteristics of sediment from a naturally reduced zone in a uranium-contaminated aquifer. Applied Geochemistry 27, 1499-1511.

Show in context

Show in contextRecently, Campbell et al. (2012) showed that non-crystalline mononuclear U(IV) is present in aquifer sediments at the Rifle site.

View in article

Cerrato, J.M., Asner, M.N., Alessi, D.S., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Bernier-Latmani, R., Bargar, J.R., Giammar, D.E. (2013) Relative reactivity of biogenic and chemogenic uraninite and biogenic non crystalline U(IV). Environmental Science and Technology 47, 9756-9763.

Show in context

Show in context The major occurrence of such species in lacustrine sediments has important environmental implications since mononuclear U(IV) species are potentially more labile than uraninite (Cerrato et al., 2013; Alessi et al., 2014a) and polymerised non-crystalline U(IV) phosphate phases (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Chappaz, A., Gobeil, C., Tessier, A. (2010) Controls on uranium distribution in lake sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 74, 203-214.

Show in context

Show in context Studies of uranium distribution in lacustrine environments suggested associations of U with organic matter in bottom lake sediments (Ueda et al., 2000; Chappaz et al., 2010) as well as in the water column (Alberic et al., 2000) but no direct determinations of uranium speciation in such environments have been yet reported.

View in article

Doinikova, O.A. (2007) Uranium Deposits with a new phosphates types of blacks. Geology of Ore Deposits 49, 80-86.

Show in context

Show in context Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

Doinikova, O.A., Sidorenko, G.A., Sivtsov, A.V. (2014) Phosphosilicates of tetravalent uranium. Doklady Earth Sciences 456, 755–758.

Show in context

Show in context In the mineral phase identified here, the excess of U4+ over Ca2+ is likely compensated by SiO44- for PO43- substitution, as in Si-rich ningyoite (Doinikova et al., 2014).

View in article

Fletcher, K.E., Boyanov, M.I., Thomas, S.H., Wu, Q., Kemner, K.M., Löffler, F.E. (2010) U(VI) reduction to mononuclear U(IV) by Desulfitobacterium species. Environmental Science and Technology 44, 4705-4709.

Show in context

Show in context In laboratory bioassays, mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate complexes, in which a U(IV) ion coordinates to a PO4 group, have been especially observed as products of microbial uranyl reduction (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011).

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Kelly, S.D, Kemner, K.M., Carley, J., Criddle, C., Jardine, P.M., Marsh, T.L., Phillips, D., Watson, D., Wu, W.M. (2008) Speciation of uranium in sediments before and after in situ biostimulation. Environmental Science and Technology 42, 1558-1564.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Khijniak, T.V., Slobodkin, A.I., Coker, V., Renshaw, J.C., Livens, F.R., Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A., Birkeland, N.K., Medvedeva-Lyalikova, N.N., Lloyd, J.R. (2005) Reduction of Uranium(VI) Phosphate during Growth of the Thermophilic Bacterium Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 6423-6426.

Show in context

Show in context U(IV)-phosphate mineral phases as ningyoite CaU(PO4)2•2H2O have also been identified after microbial reduction of dissolved uranyl in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010) or after reduction of uranyl phosphate mineral phases (Khijniak et al., 2005; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems.

View in article

Lee, S.Y., Baik M.H., Choi, J.W. (2010) Biogenic formation and growth of uraninite (UO2). Environmental Science and Technology 44, 8409-8414.

Show in context

Show in context U(IV)-phosphate mineral phases as ningyoite CaU(PO4)2•2H2O have also been identified after microbial reduction of dissolved uranyl in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010) or after reduction of uranyl phosphate mineral phases (Khijniak et al., 2005; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011) U(VI) reduction.

View in article

The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems.

View in article

Muto, T., Meyrowitz, R., Pommer, A., Murano, T. (1959) Ningyoite, a new uranous phosphate mineral from Japan. American Mineralogist 44, 633-650.

Show in context

Show in context According to Muto et al. (1959), powder XRD data of ningyoite [CaU(PO4)2•2H2O] indicate that this mineral is isostructural to rhabdophane [REE3+PO4•H2O], with an equivalent amount of U4+ and Ca2+ ions substituting for the REE3+ ions.

View in article

Newsome, L., Morris, K., Lloyd, J.R. (2014) The biogeochemistry and bioremediation of uranium and other priority radionuclides. Chemical Geology 363, 164-184.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Qafoku, N.P., Nikolla, P., Kukkadapu, R.K., Ravi, K., Mckinley, J.P., James, P., Arey, B.W., Kelly, S.D., Wang, C.M., Resch, C.T., Long, P.E. (2009) Uranium in framboidal pyrite from a naturally bioreduced alluvial sediment. Environmental Science and Technology 43, 8528-8534.

Show in context

Show in context The occurrence and distribution of non-uraninite U(IV) phases in natural systems is however scarcely documented (Qafoku et al., 2009).

View in article

Rui, X., Kwon, M.J., O'Loughlin, E.J., Dunham-Cheatham, S., Fein, J.B., Bunker, B., Kemner, K. M., Boyanov, M.I. (2013) Bioreduction of Hydrogen Uranyl Phosphate: Mechanisms and U(IV) Products. Environmental Science and Technology 47, 5668-5678.

Show in context

Show in context U(IV)-phosphate mineral phases as ningyoite CaU(PO4)2•2H2O have also been identified after microbial reduction of dissolved uranyl in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010) or after reduction of uranyl phosphate mineral phases (Khijniak et al., 2005; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

Most ningyoite ore deposits are suspected to have formed in reducing zones close to the anoxic-oxic boundary, possibly via microbial activity (Doinikova, 2007) as suggested by laboratory experiments (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Rui et al., 2013).

View in article

The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011) U(VI) reduction.

View in article

The absence of uraninite in the sediments studied here supports previous laboratory studies attesting that phosphate ions can inhibit uraninite precipitation (Khijniak et al., 2005; Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013), and suggest that silicate could act similarly in natural systems.

View in article

Such a phase could have formed in the sediment after bioreduction of either soluble U(VI) (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010) or, more likely, of a secondary U(VI)-phosphate/silicate mineral inherited from the uranium ore (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. S-1).

View in article

Sharp, J.O., Lezama-Pcheco, J.S., Schofield, E.J., Junier, P., Ulrich, K-U., Chinni, S., Veeramani, H., Margot-Roquier, C., Webb, S.M., Tebo, B.M., Giammar, D.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) et Uranium speciation and stability after reductive immobilization in aquifer sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 6497-6510.

Show in context

Show in context Ex situ incubations of aquifer sediments under anoxic conditions have highlighted the importance of non-crystalline U(IV) species as major products of microbial reduction of uranyl (Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Sivaswamy, V., Boyanov, M.I., Peyton, B.M., Viamajala, S., Gerlach, R., Apel, W.A., Sani, R.K., Dohnalkova, A., Kemner, K.M., Borch, T. (2011) Multiple Mechanisms of Uranium Immobilization by Cellulomonas sp. Strain ES6. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 108, 264-276.

Show in context

Show in context In laboratory bioassays, mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate complexes, in which a U(IV) ion coordinates to a PO4 group, have been especially observed as products of microbial uranyl reduction (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011).

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Suzuki, Y., Kelly, S.D., Kemner, K.A., Banfield, J.F. (2005) Microbial populations stimulated for hexavalent uranium reduction in uranium mine sediment. Applied Environmental Microbiology 69, 1337-1346.

Show in context

Show in contextResearchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Ueda, S., Hasegawa, H., Iyogi, T., Kawabata, H., Kondo, K. (2000) Investigation of physicochemical form of uranium in sediment of brackish Lake Obushi using sequential extraction procedure. Limnology 13, 231-236.

Show in context

Show in contextStudies of uranium distribution in lacustrine environments suggested associations of U with organic matter in bottom lake sediments (Ueda et al., 2000; Chappaz et al., 2010) as well as in the water column (Alberic et al., 2000) but no direct determinations of uranium speciation in such environments have been yet reported.

View in article

Veeramani, H., Alessi, D., Suvorova, E., Lezama-Pacheco, J., Stubbs, J., Dippon, U., Kappler, A., Bargar, J., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2011) Products of abiotic U(VI) reduction by biogenic magnetite and vivianite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 2512-2528.

Show in context

Show in context The observed U-P/Si distance of ~3.1 Å corresponds to edge-sharing bidentate bridging of the UO8 group to a PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron (Rui et al., 2013) (Fig. 4b, Table S-4), such U-P distance being characteristic of non-uraninite U(IV) species identified as products of microbial (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Boyanov et al., 2011) or abiotic (Veeramani et al., 2011) U(VI) reduction.

View in article

Importantly, we show the predominance of mononuclear U(IV)-phosphate/silicate species, in agreement with results of laboratory studies involving U(VI) reduction in the presence of phosphate (Bernier-Latmani et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Sivaswamy et al., 2011; Boyanov et al., 2011; Veeramani et al., 2011; Sharp et al., 2011; Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Such U(IV) mononuclear species could either be sorbed to the surface of phosphate (Veeramani et al., 2011) as well as silicate minerals, or be bound to organic phosphoryl groups (Alessi et al., 2014b).

View in article

Wu, W.M., Carley, J., Luo, J., Ginder-Vogel, M.A., Cardenas, E., Leigh, M.B., Hwang, C.C., Kelly, S.D., Ruan, C.M., Wu, L.Y., Van Nostrand, J., Gentry, T., Lowe, K., Mehlhorn, T., Carroll, S., Luo, W.S., Fields, M.W., Gu, B.H., Watson, D., Kemner, K.M., Marsh, T., Tiedje, J., Zhou, J.Z., Fendorf, S., Kitanidis, P.K., Jardine, P.M., Criddle, C.S. (2007) In situ bioreduction of uranium(VI) to submicromolar levels and reoxidation by dissolved oxygen. Environmental Science and Technology 41, 5716-5723.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

Yabusaki, S.B., Fang, Y., Long, P.E., Resch, C.T., Peacock, A.D., Komlos, J., Jaffe, P.R., Morrison, S.J., Dayvault, R.D., White, D.C., Anderson, R.T. (2007) Uranium removal from groundwater via in situ biostimulation: field-scale modeling of transport and biological processes. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 93, 216-235.

Show in context

Show in context Researchers addressing remediation of U-contaminated groundwaters have focused on in situ biostimulation strategies involving microbial reduction of U(VI) (Wu et al., 2007; Yabusaki et al., 2007) into biogenic uraninite (Suzuki et al., 2005; Bargar et al., 2008) as well as non-uraninite U(IV) phases (Kelly et al., 2008; Alessi et al., 2014a; Bargar et al., 2013; Newsome et al., 2014).

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

SI-1: Chemical Analyses Procedures

Sample 2011_190-194cm was analysed for uranium content using the following procedure. Prior to ICP-MS analysis, about 50 mg of powdered sample were dissolved in 2 mL of concentrated HF–HNO3 mixture, heated at 90 °C for 1h and then evaporated to dryness at 60 °C. The residue was dissolved in 1 mL of HNO3–H3BO3 mixture and slowly evaporated at 60 °C to remove possible weakly soluble fluorides. The new residue was dissolved in 2 % HNO3 for analysis. Trace element compositions of the digested samples were measured by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) using a X Series II instrument of Thermo Scientific at the University Pierre & Marie Curie.

Samples 2012_120-123 cm and 2012_143-146 cm were analysed for uranium content at the SARM-CRPG laboratory (Nancy, France) by ICP-MS Thermo Elemental X7. The powdered samples were fused with LiBO2 and dissolved with HNO3 prior to analysis. Major elements were analysed by ICP-OES Thermo Fisher ICap 6500. Details on the analytical procedures can be found at http://www.crpg.cnrs-nancy.fr/SARM/.

SI-2: Selective Chemical Extraction Procedure

Non-crystalline U(IV) species were extracted by reacting 0.1 g of sediment sample with 10 mL of an O2-free NaHCO3 1M solution under gentle shaking for 24 hours in an anoxic glove box according to a protocol adapted from Alessi et al. (2012)

Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

. Supernatants were recovered by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min and filtered through 0.2 µm. An aliquot of 0.5 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 4.5 mL of 1.0 M HNO3. Dissolved uranium concentrations were then measured by ICP-MS after 100 to 1000 times dilution into 0.1 M HNO3.SI-3: Mineralogical Analyses Procedures

Scanning Electron Microscopy analyses were performed using a Zeiss ultra 55 equipped with a Field Emission Gun (FEG) operating at 15 kV with a working distance of 7.5 mm. Images were collected in backscattering mode using the AsB detector. Semi-quantitative analysis of the Energy Dispersive X-ray spectra was performed using the Bruker® Esprit program, by comparison with a standard spectra database and after absorption correction using the Phi(rho,z) method. Calibration of the beam intensity was done using the X-ray emission from a copper grid.

SI-4: Model Compounds Synthesis Procedures

Biogenic uraninite was produced under anoxic conditions at neutral pH by reducing 1.5 mM of uranyl acetate (UO2(CH3COO-)2•2H2O) in the presence of 20 mM of sodium methanoate as the electron source using a dissimilatory iron-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (5.7 × 108 CFU/mL). The experimental procedures and the composition of the basic medium were similar to those followed by Ona-Nguema et al. (2002)

Ona-Nguema, G., Abdelmoula, M., Jorand, F., Benali, O., Géhin, A., Block, J.-C., Génin, J.-M.R. (2002) Iron(II,III) hydroxycarbonate green rust formation and stabilization from lepidocrocite bioreduction. Environmental Science and Technology 36, 16-20.

and Ona-Nguema et al. (2009)Ona-Nguema, G., Morin, G., Wang, Y., Menguy, N., Juillot, F., Olivi, L., Aquilanti, G., Abdelmoula, M., Ruby, C., Bargar, J.R., Guyot, F., Calas, G., Brown, J.R.G.E. (2009) Arsenite sequestration at the surface of nano-Fe(OH)2, ferrous-carbonate hydroxide, and green-rust after bioreduction of arsenic-sorbed lepidocrocite by Shewanella putrefaciens. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 1359-1381.

, with exception of the nature of strain used. The cultures were buffered with 30 mM of NaHCO3 and 20 mM of 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES) as described by Schofield et al. (2008)Schofield, E.J., Veeramani, H., Sharp, J.O., Suvorova, E., Bernier-Latmani, R., Mehta, A., Stahlman, J., Webb, S.M., Clark, D.L., Conradson, S.D. (2008) Structure of biogenic uraninite produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Environmental Science and Technology 42, 7898-7904.

. After 24 hours, the solids were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 rpm and vacuum-dried in a dryer placed into a glove-box. The solid was then treated using an O2-free NaHCO3 1M solution to remove non-crystalline U species (Alessi et al., 2012Alessi, D.S., Uster, B., Veeramani, H., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Stubbs, J.E., Bargar, J.R., Bernier-Latmani, R. (2012) Quantitative Separation of Monomeric U(IV) from UO2 in Products of U(VI) Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology 46, 6150-6157.

) and washed three times with O2-free deionised water, in order to obtain the solid sample referred to as bio-UO2.Acidic U(IV) stock solutions. A 74 mM U(IV) chloride solution was prepared by dissolving 20 mg of bio-UO2 into 1 mL of 37 % HCl. A 0.2 mM U(IV) chloride solution was prepared by dissolving 5.4 mg of bio-UO2 into 1 mL of 37 % HCl and completing to 100 mL with O2-free deionised water.

U(IV) humic acid + UO2 referred to as “U(IV)/HA + UO2” was obtained in a Jacomex® anoxic glove box by reacting purified peat humic acid (HA) from Suwanee River obtained from International Humic Substances Society (IHSS) with a 5 10-6 M U(IV) solution at acidic pH and rising the pH to 6. For this purpose, 40mg PPHA was first solubilised in 40 mL O2-free H2O at pH 8 under shaking for 24 h. The PPHA solution was then adjusted to pH 3.5 using O2-free 0.1 M HCl. A volume of 1 mL of a 0.2 mM U(IV) chloride O2-free solution at pH 1.5 was then added dropwise to the acidified PPHA solution and the pH was then adjusted to 6.5 using a 0.2M NaOH O2-free solution. The solution was then stirred for 1 h before being evaporated at room temperature under vacuum in the glove box to obtain U(IV)-HA as a solid paste.

U(IV) citrate was prepared in a Jacomex® anoxic glove box by mixing 1.5 mL of a 260 mM citric acid O2-free solution at pH 2 (100 mg sodium citrate in 1 mL H2O + 0.5 mL 35 wt.a % HCl), with 4 mL of a 0.2 mM U(IV) chloride O2-free solution at pH 1.5, and raising the pH of the mixture to 6.5 with an appropriate volume of 1M NaOH O2-free solution. The mixed solution was then stirred for 1 h and then evaporated under vacuum within the glove box to obtain U(IV)-citrate as a solid paste.

U(IV) pyrophosphate was prepared in a Jacomex® anoxic glove box by mixing 2.5 mL of a 150 mM pyrophosphoric acid O2-free solution at pH ~2 (100 mg sodium pyrophosphate in 2 mL deionised O2-free H2O + 0.5 mL 85 wt. % H3PO4), with 4 mL of a 0.2 mM U(IV) chloride O2-free solution at pH 1.5, and raising the pH of the mixture to the value of 6.5 with an appropriate volume of 1M NaOH O2-free solution. The mixed solution was stirred for 1 h and then evaporated under vacuum within the glove box to obtain U(IV)-citrate as a solid paste.

U(VI) pyrophosphate was prepared similarly as the U(IV) pyrophosphate sample but replacing the 4 mL of 0.2 mM U(IV) chloride solution by 0.4 mL of a 2 mM uranyl nitrate solution.

Amorphous CaU(PO4)2•nH2O, was prepared in a Jacomex® anoxic glove box by mixing 20 mL of a 0.74M H3PO4 O2-free solution at pH ~0.8, with 1 mL of a 74 mM U(IV) chloride O2-free solution at pH -1 and with 0.74 mL of 0.01 M CaCl2 O2-free solution. The pH was then adjusted to 5 using NaOH O2-free solution with decreasing molarities and the solution was stirred for 1 hour. The solid was harvested by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 15 min, washed 3 times with O2-free deionised H2O and vacuum-dried in the glove box.

SI-5: X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) Data Collection