Nickel accelerates pyrite nucleation at ambient temperature

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding informationKeywords: pyrite, mackinawite, iron sulphides, nickel, kinetics, nucleation, solid-solution, low temperature, sediments, early diagenesis, EXAFS, TEM-HAADF

- Share this article

Article views:9,692Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

Abstract

Figures and Tables

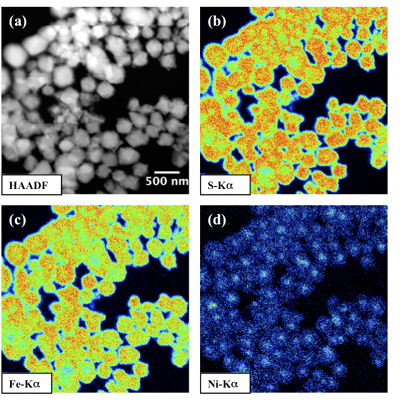

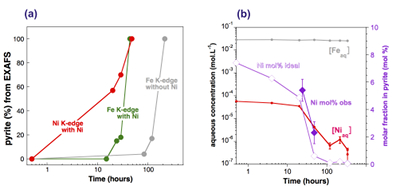

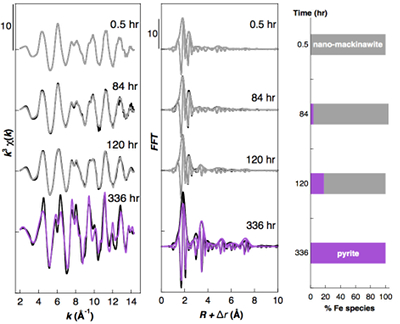

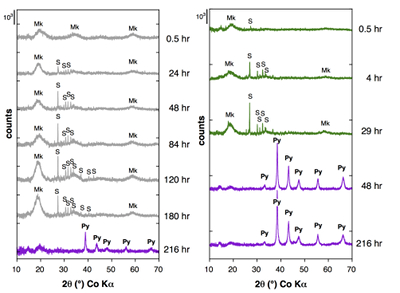

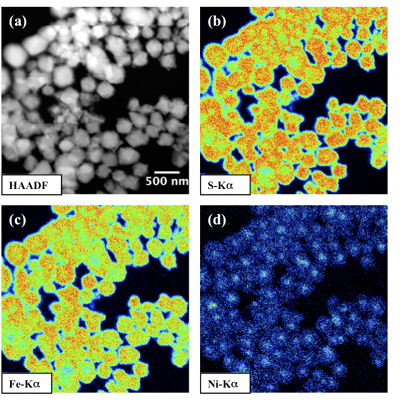

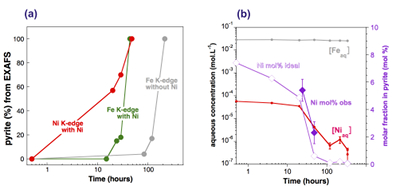

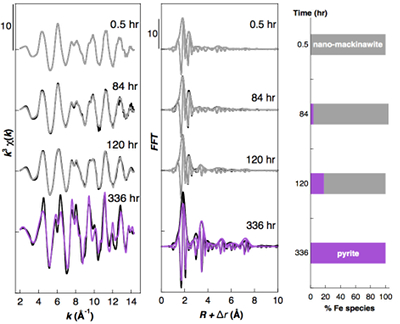

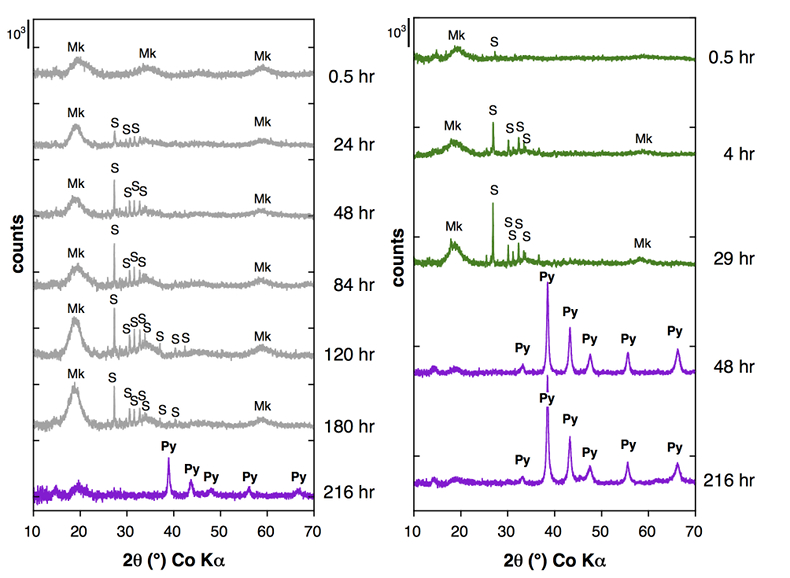

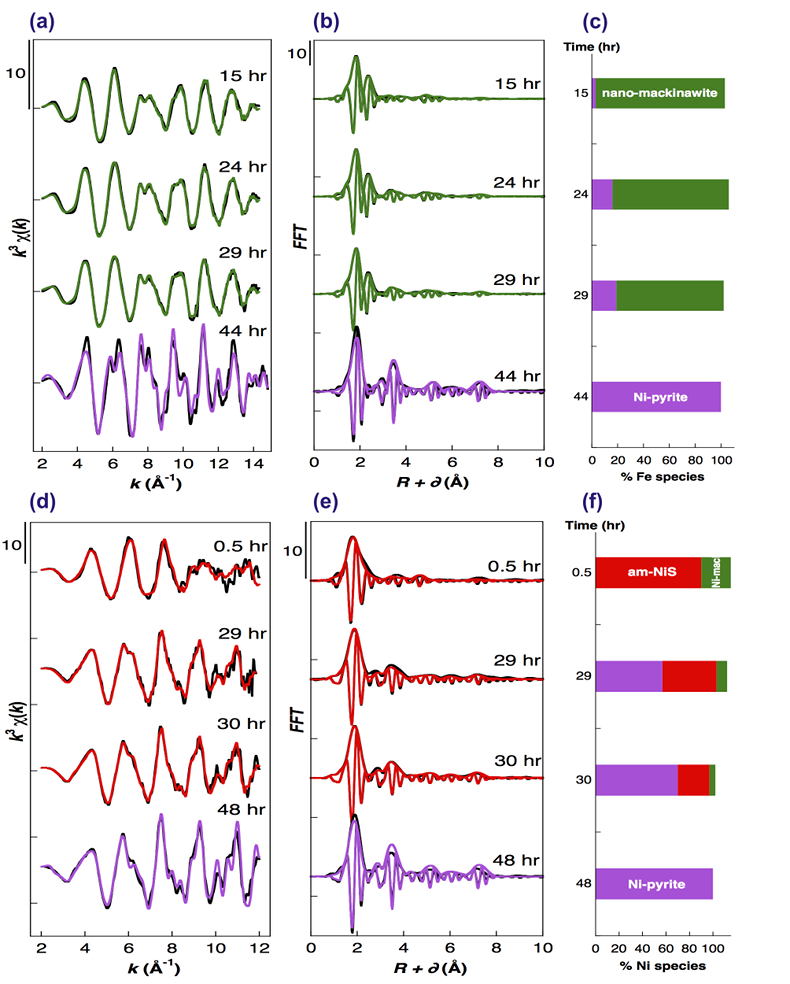

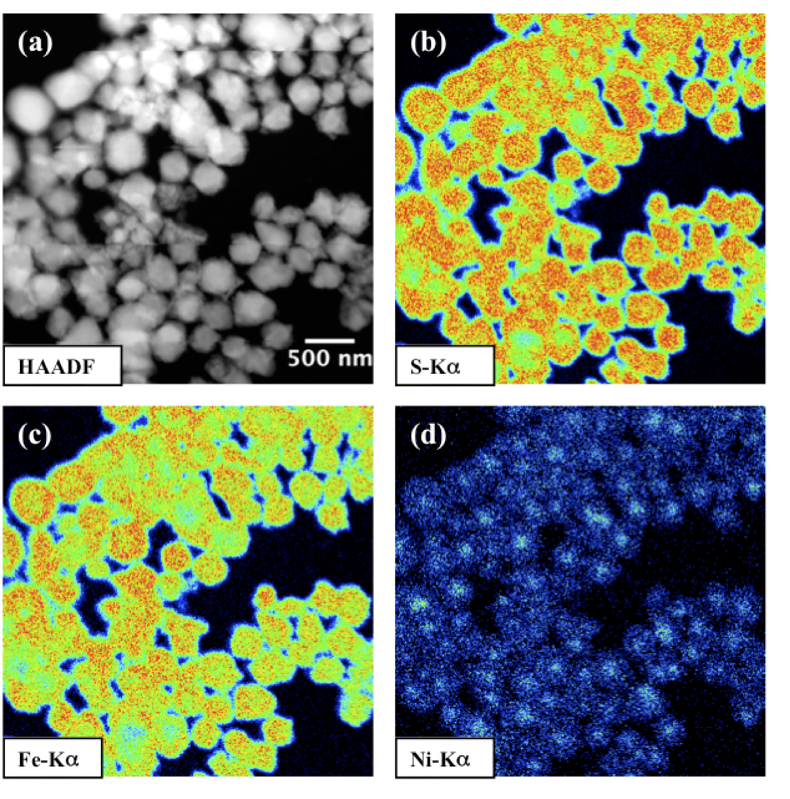

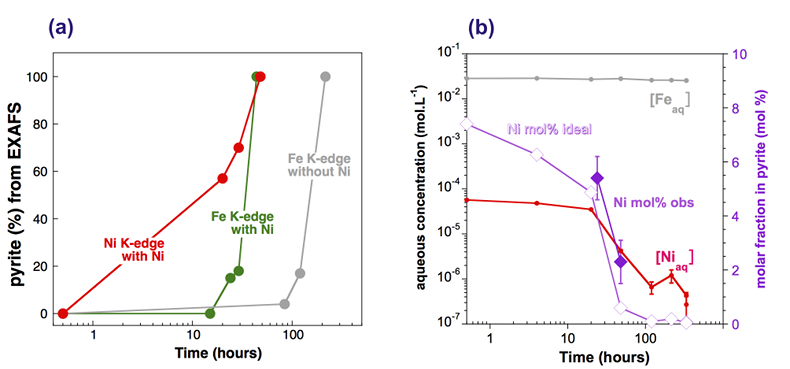

Figure 1 Aqueous nickel impurity accelerates the formation of pyrite from a FeS(m) precursor. Powder XRD patterns of the solids collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted at room temperature in the absence (left) or presence (right) of aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Mk: nano-mackinawite; S: a-sulphur; Py: pyrite. |  Figure 2 Fe and Ni speciation in the solids formed during the synthesis of Ni-doped pyrite. Fe (a,b) and Ni (d,e) K-edge k3-weighted EXAFS spectra and corresponding Fast Fourier transforms. Experimental (black). Ab initio Feff8.1 calculation (purple) (Table S-3). LC-LS fits (green: Fe; red: Ni) (Table S-4). LC-LS fit components probing the local structure around Fe (c) and Ni (f) atoms include: Ni-pyrite (Fe1-xNixS2), am-NiS (amorphous NiS) and Ni-mack (Fe1-xNixS) (Table S-4). |  Figure 3 Compositional zoning of the pyrite nanocrystals. STEM-HAADF images and TEM-EDXS mapping of the pyrite particles collected at 48 hr, from the experiment performed with aqueous Ni. Elemental maps show that Ni is preferentially located into the core of the pyrite crystals. Elemental abundances increase from blue to green and to red colours. |  Figure 4 Distribution of Ni and Fe in the solid and dissolved phases during the pyrite synthesis. (a) Proportion of initial Ni (red) and Fe (green and gray) incorporated in pyrite in the synthesis conducted with and without Ni impurity, as determined by LC-LS fits of EXAFS data (Figs. 2 and S-2). (b) Concentrations of aqueous Fe ([Feaq]) and Ni ([Niaq]) in the presence (with Ni) and absence (without Ni) of aqueous Ni impurity. The molar fraction of Ni in pyrite estimated by combining chemical composition of the solution and EXAFS analysis of the solids (Ni mol. % obs; purple diamonds) is compared to the molar fraction of Ni in pyrite predicted by assuming saturation equilibrium with an ideal pyrite-vaesite solid solution (Ni mol. % ideal; white diamonds) (see text and Table S-5). |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

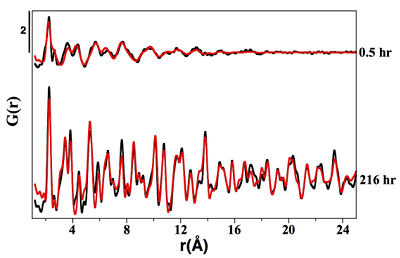

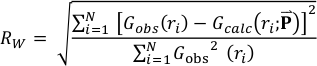

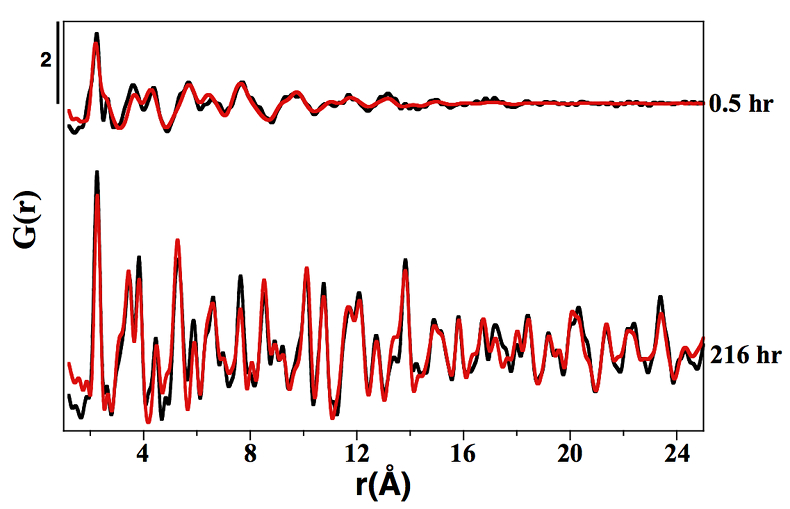

Table S-1 Proportions of the reactants used for the two pyrite synthesis experiments performed without or with aqueous Ni2+ impurity in the starting solution. All solutions were prepared with O2-free milli-Q water in an anaerobic chamber. Appropriate volumes (v) of metal cation stock solutions of concentrations (c) were mixed with 42 mL of O2-free milli-Q water under stirring and completed with 4 mL of Na2S solution to 50 mL total volume (VTotal) in glass vials. These vials with initial concentrations of the reactants (C) were then sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and reacted for two weeks at 25 °C under constant strirring. Solution pH at the start and end of the synthesis experiments are also reported. |  Figure S-1 PDF analysis of the samples collected at 0.5 hr and 216 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment. For the 0.5 hr and 216 hr samples, the best fits were obtained from the refinement in real space of the mackinawite structure (Lennie et al., 1995) and the pyrite structure (Wyckoff et al., 1963) respectively (Table S-2). Experimental and calculated PDF curves are plotted in black and red colours, respectively. |  Table S-2 Refined crystallographic parameters obtained from the PDF analysis of the samples collected at 0.5 hr and 216 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment, using the mackinawite (Lennie et al., 1995) and pyrite (Wyckoff et al., 1963) structures as starting models, respectively. |  Table S-3 Crystallographic data used for ab initio Feff8.1 calculations of Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data for the synthetic Ni-free and Ni-doped pyrite end products. Corresponding k3χ(k) EXAFS and FFT curves are plotted in Figure S-2 as well as in Figure 2a,b and in Figure 2c,d, for the Fe and Ni K-edge data, respectively. Interatomic distances between the central Fe or Ni atom and its closest neighbours in the cluster are reported. To adjust the amplitude and the energy position of the EXAFS spectra, an overall Debye-Waller parameter σ and a threshold energy shift ∆E0 parameter were simultaneously refined. The S02 parameter was fixed to 1. Fit quality was estimated using an R-factor (Rf) and uncertainty on the refined parameters are given in parentheses (see text). |

| Table S-1 | Figure S-1 | Table S-2 | Table S-3 |

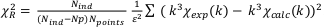

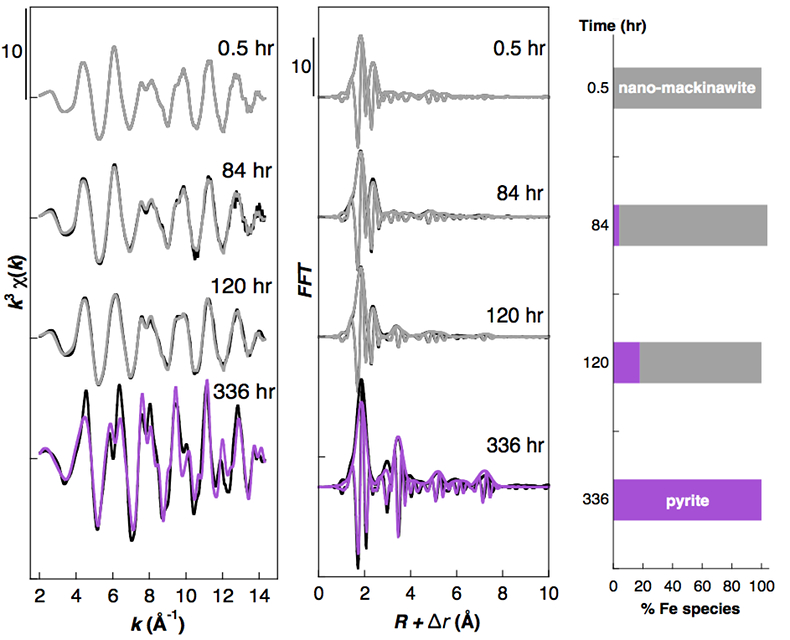

Figure S-2 Fe K-edge k3-weighted EXAFS data of the solid samples collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted without aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Experimental k3χ(k) functions (left panel) and corresponding Fast Fourier Transforms (centre panel) are displayed as black lines. Ab initio calculation of the EXAFS spectra of the pyrite end product is displayed in purple (Table S-3). Linear combination least squares (LC-LS) fits of the solid samples collected over the course of the synthesis experiments are displayed in gray curves. Proportions of the LC-LS fitting components (right panel) are reported in Table S-4. |  Table S-4 Results of LC-LS fits for Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data of the solids collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted with (Fig. 2) or without (Fig. S-2) aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Results are given in percentage of the following fitting components: the nanocrystalline mackinawite (nano-mack) collected at 0.5 hr in the Ni-free experiment; the pyrite end product of the Ni-free experiment (pyrite), the Ni-doped pyrite end product of the experiment conducted with Ni (Ni-doped pyrite), amorphous NiS (am-NiS), nanocrystalline Ni-doped mackinawite (Ni-Mack). Using vaesite NiS2 as fitting component did not match the data. Uncertainties on the component proportions are given in brackets for the last digit. Goodness of fit is evaluated by a reduced χ2R (see SI text). |  Table S-5 Solubility data for relevant Fe and Ni sulphide solid phases and aqueous species used in the aqueous chemistry calculation displayed in Figure 4. Dissolution reactions are written in terms of HS-, SO42-, S(0), Fe2+ and Ni2+ for consistency with the Chess code database. The equilibrium constants of these reactions have been converted from reported reactions and constants given below. |  Table S-6 Composition of the Fe1-xNixS2 solid solutions derived from saturation equilibrium with respect to the aqueous concentrations of Fe ([Feaq]) and Ni ([Feaq]) measured by ICP-MS over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiment conducted in the presence of Ni. Molar fractions of Ni (x ideal) and Fe ((1-x) ideal) in the ideal solid solution were predicted assuming a theoretical partition coefficient (Bruno et al., 2007): Dideal = KsPy /KsVa = [Feaq]/[Niaq] • x/(1-x) = 39 (See Table S-5 for solubility constants). Observed molar fractions of Ni (x obs) and Fe ((1-x) obs) in the synthesised pyrite were derived from the fractions of Ni and Fe in the solid phase weighted by the proportion of total Fe or Ni in pyrite derived from EXAFS analysis (Table S-4 and Fig. 3). [Fe0] = 50mM and [Ni0] = 500 µM (Table S-1). |

| Figure S-2 | Table S-4 | Table S-5 | Table S-6 |

top

Introduction

Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005

Rouxel, O.J., Bekker, A., Edwards, J. (2005) Iron Isotope Constraints on the Archean and Paleoproterozoic Ocean Redox State. Science 307, 1088–1091.

; Reinhard et al., 2009Reinhard, C.T., Raiswell, R., Scott, C., Anbar, A.D., Lyons, T.W. (2009) A late Archean sulfidic sea stimulated by early oxidative weathering of the continents. Science 326, 713–716.

; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014Marin-Carbonne, J., Rollion-Bard, C., Bekker, A., Rouxel, O., Agangi, A., Cavalazzi, B., Wohlgemuth-Ueberwasser, C.C., Hofmann, A., McKeegan, K.D. (2014) Coupled Fe and S isotope variations in pyrite nodules from Archean shale. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 392, 67–79.

), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005Catling, D.C. and Claire, M.W. (2005) How Earth’s atmosphere evolved to an oxic state: A status report. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 237, 1–20.

; Ohmoto et al., 2006Ohmoto, H., Watanabe, Y., Ikemi, H., Poulson, S.R., Taylor B.E. (2006) Sulphur isotope evidence for an oxic Archaean atmosphere. Nature Letter 442, 908–911.

) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008Johnson, C.M., Beard, B.L., Roden, E.E. (2008) The Iron Isotope Fingerprints of Redox and Biogeochemical Cycling in Modern and Ancient Earth. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science 36, 457–493.

). Moreover, trace metals incorporated in pyrite have been recognised as proxies for ancient ocean chemistry (Large et al., 2017Large, R.R., Mukherjee, I., Gregory, D.D., Steadman, J.A., Maslennikov, V.V., Meffre, S. (2017) Ocean and Atmosphere Geochemical Proxies Derived from Trace Elements in Marine Pyrite: Implications for Ore Genesis in Sedimentary Basins. Economic Geology, 112, 423–450.

). Besides, the formation of pyrite from a (Fe,Ni)S precursor has been proposed to be involved in the ‘Fe-S World’ theory of the origin of life (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1997) Acetic Acid by Carbon Fixation on (Fe,Ni)S Under Primordial Conditions. Science 276, 245–247.

, 1998Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1998) Peptides by Activation of Amino Acids with CO on (Ni,Fe)S Surfaces: Implications for the Origin of Life. Science 281, 670–672.

). In parallel, nickel has been recognised as an essential biocatalytic metal agent in iron-sulphur enzymes, especially acetyl-CoA synthase, which is a major enzyme of acetogenic bacteria and methanogens for fixing CO/CO2 (Darnaud et al., 2003Darnaud, C., Volbeda, A., Kim, E.J., Legrand, P., Vernède, X., Lindahl, P.A., Fontecilla-Camps, J.C. (2003) Ni-Zn-[Fe4-S4] and Ni-Ni-[Fe4-S4] clusters in closed and open α subunits of acetyl-CoA synthase/carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. Nature Structural Biology 10, 271–279.

). Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992Huerta-Diaz, M.A., Morse, J.W. (1992) Pyritization of trace metals in anoxic marine sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 56, 2681–2702.

; Morse and Luther, 1999Morse, J.W., Luther III, G.W. (1999) Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 63, 3373–3378.

; Large et al., 2017Large, R.R., Mukherjee, I., Gregory, D.D., Steadman, J.A., Maslennikov, V.V., Meffre, S. (2017) Ocean and Atmosphere Geochemical Proxies Derived from Trace Elements in Marine Pyrite: Implications for Ore Genesis in Sedimentary Basins. Economic Geology, 112, 423–450.

), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014Noël, V., Marchand, C., Juillot, F., Ona-Nguema, G., Viollier, E., Marakovic, G., Olivi, L., Delbes, L., Gelebart, F., Morin, G. (2014) EXAFS analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream of a lateritized ultramafic watershed (Vavouto Bay, New Caledonia). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 136, 211–228.

, 2015Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

). The image that arises is one in which pyrite is a regulator of iron and trace metal distribution in modern and ancient environments. Conversely, the possible effects of metal impurities such as nickel on the formation of pyrite have not been investigated yet, especially at low-temperature (Morse and Luther, 1999Morse, J.W., Luther III, G.W. (1999) Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 63, 3373–3378.

; Rickard and Luther, 2007Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

). Here we show that Ni2+ as impurity drastically accelerates pyrite formation at ambient temperature under early diagenesis-like conditions, thus suggesting that Ni impurities might have influenced the distribution and abundance of pyrite and nickel in the present and ancient sedimentary record.top

Materials and Methods

Pyrite (FeS2) was synthesised by reacting ferric chloride with sodium sulphide in aqueous solution for two weeks at room temperature under strict anoxic conditions (Noël et al., 2014

Noël, V., Marchand, C., Juillot, F., Ona-Nguema, G., Viollier, E., Marakovic, G., Olivi, L., Delbes, L., Gelebart, F., Morin, G. (2014) EXAFS analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream of a lateritized ultramafic watershed (Vavouto Bay, New Caledonia). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 136, 211–228.

, 2015Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

), with or without nickel chloride as impurity (Ni/Fe = 0.01 mol/mol) in the starting solution (∑Fe(III) + Ni(II) = ∑S(-II) = 50 mM at pH 5.5; Table S-1). Over the course of pyrite formation, the solid and aqueous phases were sampled by centrifugation and 0.2 µm filtration. Aqueous Fe and Ni concentrations were measured by ICP-AES and HR-ICP-MS, respectively. The mineralogy of the solid samples was determined by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) - pair distribution function (PDF) under anoxic conditions. The nano-scale distribution of Fe and Ni was mapped by scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) in high angle annular dark field (HAADF) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXS). The molecular environment of Ni and Fe was probed by using extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy. EXAFS spectra of the pyrite end products were least squares fitted to theoretical ab initio spectra calculated with the Feff8.1 code. EXAFS spectra of the solids collected over the course of the experiments were analysed by linear combination least squares (LC-LS) fitting using a large model compounds spectra database (Noël et al., 2014Noël, V., Marchand, C., Juillot, F., Ona-Nguema, G., Viollier, E., Marakovic, G., Olivi, L., Delbes, L., Gelebart, F., Morin, G. (2014) EXAFS analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream of a lateritized ultramafic watershed (Vavouto Bay, New Caledonia). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 136, 211–228.

, 2015Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

). Detailed procedures are reported in Supplementary Information.top

Results and Discussion

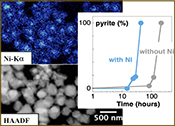

Mineralogical sequence leading to pyrite formation. The first solid phase that formed in our pyrite synthesis experiments was nanocrystalline mackinawite, FeS(m) (Lennie et al., 1995

Lennie, A.R., Redfern, S.A.T., Schofield, P.F., Vaughan, D.J. (1995) Synthesis and Rietveld crystal structure refinement of mackinawite. Mineralogical Magazine 59, 677–683.

; Rickard and Luther, 2007Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

), rapidly followed by the crystallisation of minor amounts of S(0)(alpha) (Fig. 1). After an extended lag phase, pyrite rapidly formed at the expense of FeS(m) and S(0)(alpha), and was produced as a single phase at the end of all experiments (Figs. 1, S-1 and Table S-2). Fe K-edge EXAFS spectra of the Ni-free (Fig. S-2 and Table S-3) and of the Ni-doped end products (Fig. 2b and Table S-3) well matched pyrite crystallographic data (Wyckoff, 1963Wyckoff, R.W.G. (1963) Crystal Structures. Second Edition, Volumes 1–6. Interscience, New York.

).This mineralogical sequence is consistent with pyrite formation pathways at low temperature via a FeS(m) precursor (Berner, 1970

Berner, R.A. (1970) Sedimentary pyrite formation. American Journal of Science 268, 1–23.

; Rickard, 1975Rickard, D.T. (1975) Kinetics and mechanism of pyrite formation at low-temperature. American Journal of Science 275, 636–652.

; Schoonen and Barnes, 1991Schoonen, M.A.A., Barnes, H.L. (1991) Reactions forming pyrite and marcasite fom solution 2. Via FeS precursors below 100°C. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 55, 1505–1514.

). Accordingly, in our experiments, Fe(III) species rapidly reacted with aqueous H2S to form iron monosulphide FeS(m) and S(0)(alpha):Eq. 1

Fe(OH)2+(aq) + H2S(aq) ⇆ ½ FeS(m) + ½ S(0)(alpha) + ½ Fe2+(aq) + 2 H2O(l)

After the lag phase, FeS(m) then fully converted to FeS2(pyrite) as summarised by:

Eq. 2

½ FeS(m) + ½ S(0)(alpha) ⇆ ½ FeS2(pyrite)

According to Rickard (1975)

Rickard, D.T. (1975) Kinetics and mechanism of pyrite formation at low-temperature. American Journal of Science 275, 636–652.

, this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975Rickard, D.T. (1975) Kinetics and mechanism of pyrite formation at low-temperature. American Journal of Science 275, 636–652.

; Luther, 1991Luther, G.W. (1991) Pyrite synthesis via polysulfide compounds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 55, 2839–2849.

; Theberge and Luther, 1997Theberge, S., Luther, G.W. (1997) Determination of the electrochemical properties of a soluble aqueous FeS species present in sulfide solutions. Aquatic Geochemistry 3, 191–211.

; Rickard and Morse 2005Rickard, D.T., Morse J. (2005) Acid volatile sulfide (AVS) Marine Chemistry 97, 141.

; Rickard and Luther, 2007Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

), e.g., for p = 1:Eq. 3

FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

Figure 1 Aqueous nickel impurity accelerates the formation of pyrite from a FeS(m) precursor. Powder XRD patterns of the solids collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted at room temperature in the absence (left) or presence (right) of aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Mk: nano-mackinawite; S: a-sulphur; Py: pyrite.

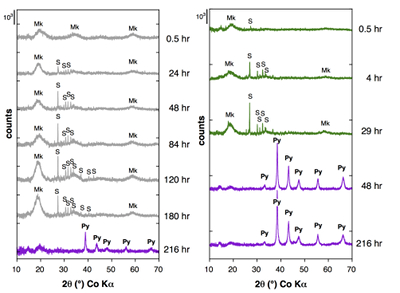

Figure 2 Fe and Ni speciation in the solids formed during the synthesis of Ni-doped pyrite. Fe (a,b) and Ni (d,e) K-edge k3-weighted EXAFS spectra and corresponding Fast Fourier transforms. Experimental (black). Ab initio Feff8.1 calculation (purple) (Table S-3). LC-LS fits (green: Fe; red: Ni) (Table S-4). LC-LS fit components probing the local structure around Fe (c) and Ni (f) atoms include: Ni-pyrite (Fe1-xNixS2), am-NiS (amorphous NiS) and Ni-mack (Fe1-xNixS) (Table S-4).

Effect of Ni2+ on pyrite nucleation. The mineralogical sequence was similar with or without the addition of Ni2+ in the starting solution, but with major changes in the kinetics of pyrite nucleation. XRD showed that Ni dramatically shortened the lag phase before pyrite formation (Fig. 1). Moreover, Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS that probed the local environment of Fe and Ni atoms at a 3–8 Å scale enabled us to catch the nucleation of pyrite before it was detected by XRD. Indeed, Fe EXAFS showed that 20 % of iron was present in pyrite clusters after 24 hours (Fig. 2a,b,c and Table S-4) for the synthesis with Ni but only after 120 hours without Ni (Fig. S-2), while pyrite was not detected by XRD at these respective reaction times (Fig. 1). Pyrite nucleation thus started ~5 times earlier with Ni than without Ni. Furthermore, Ni EXAFS showed that more than 50 % of nickel was incorporated in pyrite nuclei within the first 29 hours of the synthesis with Ni (Fig. 2d,e,f and Table S-4), before pyrite could be detected by XRD (Fig. 1). In addition, at the earliest stage of the synthesis with Ni (0.5 hr) Ni was mainly present as amorphous NiS (~80 %) with a minor fraction of Ni incorporated in nano-mackinawite (~20 %; Fig. 2 and Table S-4). At the end of the synthesis (48 hr), Ni was fully incorporated in pyrite, as indicated by the good match between experimental and ab initio calculated EXAFS spectra (Fig. 2d,e and Table S-4). Altogether, XRD and EXAFS results thus demonstrated that Ni2+ accelerated pyrite formation through the early nucleation of Ni-enriched pyrite.

Compositional zoning of the pyrite crystals at the nanoscale. STEM-EDXS mapping of the Ni-doped pyrite end product showed that Ni was preferentially located in the inner core of the pyrite crystals (Fig. 3). This was in agreement with the preferential uptake of Ni during pyrite nucleation shown by EXAFS analysis (Fig. 4a). Assuming saturation equilibrium, the composition of an ideal solid solution Fe1-xNixS2 can be predicted from the solution composition using a theoretical partition coefficient (Bruno et al., 2007

Bruno, J., Bosbach, D., Kulik, D., Navrotsky, A. (2007) Chemical thermodynamics of solid solutions of interest in radioactive waste management. A state-of-the-art report. In: Mompean, F.J., Illemassène, M. (Eds.) Chemical Thermodynamics Vol. 10. NEA TDB project, OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, Data Bank, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France.

): D = KsPy / KsVa = [Feaq]/[Niaq] • x/(1-x) (Tables S-5 and S-6). According to this model, the first pyrite nuclei should have been significantly enriched in Ni (x = 4.9 mol. % Ni ideal; Fig. 4b and Table S-6) with respect to the aqueous Ni/Fe ratio (0.013 mol. %) measured by ICP at the end of the lag phase. This enrichment that agrees with so-called “common salt effect” is consistent with the x value of 5.4 mol. % Ni observed for the first pyrite nuclei that formed after 24–29 hours, as calculated by combining EXAFS (Fig. 2 and Table S-3) and aqueous chemistry data (Table S-6). The x value of the pyrite overgrowth is then expected to have rapidly decreased after 48 hours, as confirmed by EXAFS (Fig. 4b and Table S-6), and to have almost vanished after 100 hours of synthesis (Fig. 4b and Table S-6). The compositional zoning of our synthetic Ni-doped pyrite nanocrystals (Fig. 3) can hence be interpreted as successive overgrowth of ideal solid solutions with decreasing Ni substitution rate.

Figure 3 Compositional zoning of the pyrite nanocrystals. STEM-HAADF images and TEM-EDXS mapping of the pyrite particles collected at 48 hr, from the experiment performed with aqueous Ni. Elemental maps show that Ni is preferentially located into the core of the pyrite crystals. Elemental abundances increase from blue to green and to red colours.

Figure 4 Distribution of Ni and Fe in the solid and dissolved phases during the pyrite synthesis. (a) Proportion of initial Ni (red) and Fe (green and gray) incorporated in pyrite in the synthesis conducted with and without Ni impurity, as determined by LC-LS fits of EXAFS data (Figs. 2 and S-2). (b) Concentrations of aqueous Fe ([Feaq]) and Ni ([Niaq]) in the presence (with Ni) and absence (without Ni) of aqueous Ni impurity. The molar fraction of Ni in pyrite estimated by combining chemical composition of the solution and EXAFS analysis of the solids (Ni mol. % obs; purple diamonds) is compared to the molar fraction of Ni in pyrite predicted by assuming saturation equilibrium with an ideal pyrite-vaesite solid solution (Ni mol. % ideal; white diamonds) (see text and Table S-5).

Unravelling the role of nickel in the kinetics of pyrite formation. Spontaneous pyrite nucleation is generally thought to require a saturation index as large as Log ΩPy* = 14 and/or catalytic effects (Harmandas et al., 1998

Harmandas, N.G., Navarro Fernandez, E., Koutsoukos, P.G. (1998) Crystal Growth of Pyrite in Aqueous Solutions. Inhibition by Organophosphorus Compounds. Langmuir 14, 1250.

; Rickard and Luther, 2007Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

). Within the first 30 minutes of our synthesis with Ni as impurity, amorphous NiS precipitated and a minor fraction of nickel coprecipitated with FeS(m) (Fig. 2 and Table S-4) resulting in a decrease of measured aqueous Ni and Fe concentration down to 57 µM and 28 mM, respectively (Table S-6). Based on these values that remained almost constant during the 24-29 hours lag phase (Fig. 4b), with a slight decrease for Ni (Table S-6), Chess 3.0 (van der Lee and De Windt, 2002van der Lee, J., De Windt, L. (2002) CHESS Tutorial and Cookbook. Updated for version 3.0. Users Manual Nr. LHM/RD/02/13. Ecole des Mines de Paris, Fontainebleau, France.

) calculations show that the saturation index of any ideal pyrite-vaesite solid solutions was in between the saturation indexes of the FeS2(pyrite) and NiS2(vaesite) end members (i.e. Log ΩPy = 12.3 and Log ΩVa = 9.9, respectively). This is because the solubility products of pyrite (KsPy = 10-14.2; Rickard and Luther, 2007Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

) and vaesite (KsVa = 10-15.8; Gamsjäger et al., 2005Gamsjäger, H., Bugajski, J., Gajda, T., Lemire, R.J., Preis, W. (2005) Chemical thermodynamics of Nickel. In: Mompean, F.J., Illemassène, M. (Eds.) Chemical Thermodynamics Vol. 6. Nuclear Energy Agency Data Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, North Holland Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

) differ by less than two orders of magnitude (Table S-5). Consequently, the acceleration of pyrite nucleation in our synthesis experiment with Ni cannot be explained by supersaturation with respect to the solid solution, since Log ΩVa < Log Ω Fe1-xNixS2 < Log ΩPy < Log Ω*.Interfacial energy γ is known to influence the rate of nucleation from solution (Stumm, 1992

Stumm, W. (1992) Chemistry of the solid-water interface. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

). Slightly lower γ values for pyrite (Kitchaev and Ceder, 2016Kitchaev, D.A., Ceder, G. (2016) Evaluating structure selection in the hydrothermal growth of FeS2 pyrite and marcasite. Nature Commmunications 7, 13799.

) than for vaesite (Zheng et al., 2015Zheng, J., Zhou, W., Ma, Y., Cao, W., Wang, C., Guo, L. (2015) Facet-dependent NiS2 polyhedrons on counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chemical Communications 51, 12863.

) would however imply a lower activation energy for the nucleation of pyrite than for vaesite and can thus not be invoked to explain the faster nucleation of Ni-doped pyrite compared to Ni-free pyrite.Finally, ligand exchange rates of cations correlate well with the reactivity of both divalent metal oxides (Casey et al., 1993

Casey, W.H., Banfield, J.F., Westrich, H.R., McLaughlin, L. (1993) What do dissolution experiments tell us about natural weathering? Chemical Geology 105, 1–15.

) and sulphides (Morse and Luther, 1999Morse, J.W., Luther III, G.W. (1999) Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 63, 3373–3378.

) at the solid-water interface. Casey et al. (1993)Casey, W.H., Banfield, J.F., Westrich, H.R., McLaughlin, L. (1993) What do dissolution experiments tell us about natural weathering? Chemical Geology 105, 1–15.

reported that the water exchange rate of the hydrated ion is particularly low for Ni2+ (104.4 s-1) compared to that for Fe2+ (106.5 s-1) and that this difference may explain the lower dissolution rate of Ni-oxides and orthosilicates compared to their Fe analogues. In addition, Morse and Luther (1999)Morse, J.W., Luther III, G.W. (1999) Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 63, 3373–3378.

proposed that, since Ni2+ has lower kinetics of water exchange than Fe2+, incorporation of Ni2+ into FeS2 should be kinetically favoured over precipitation of pure NiS2, as we demonstrate here.Our results dispute the common assumption that supersaturation and interfacial energy exert a major control on the kinetics of pyrite nucleation when nickel is present as impurity. They rather suggest that the reactivity of nickel impurities, possibly in the form of Ni2+aq, Fe1-xNixS or NiS, could accelerate pyrite nucleation. Further studies of the S and O ligand exchange reactions in Fe-Ni-S-H2O system are thus required to elucidate the actual mechanism of this kinetic effect.

Implications for present and ancient marine biogeochemistry. Acceleration of pyrite nucleation in the presence of nickel impurity (Figs. 1 and 2) could help explain the particular catalytic role of Ni in model reaction of the prebiotic chemistry. Indeed, when added to a FeS(m) precursor, Ni has been found to facilitate the conversion of CO and CH3SH into the activated thioester CH3–CO–SCH3 (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997

Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1997) Acetic Acid by Carbon Fixation on (Fe,Ni)S Under Primordial Conditions. Science 276, 245–247.

), as well as the formation of peptides from amino-acids (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1998Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1998) Peptides by Activation of Amino Acids with CO on (Ni,Fe)S Surfaces: Implications for the Origin of Life. Science 281, 670–672.

).In addition, we show that the accelerated nucleation of pyrite in the presence of Ni leads to a compositional zoning of the pyrite nanocrystals, with a Ni-rich core and a Ni-depleted outer shell almost devoid of Ni compared to the average crystal (Fig. 3). Consequently, the Ni/Fe molar ratio in the aqueous solution after the precipitation of such inhomogeneous pyrite is 2000 times lower than the starting ratio of 0.01 in our synthesis (Fig. 4b). This effect is expected to dramatically decrease Ni concentration in the aqueous phase during early diagenesis of euxinic sediments, which may have important implications for the preservation of marine water quality. For instance, fast incorporation of Ni in pyrite could explain the efficiency of this trapping process in mangrove sediments (Noël et al., 2014

Noël, V., Marchand, C., Juillot, F., Ona-Nguema, G., Viollier, E., Marakovic, G., Olivi, L., Delbes, L., Gelebart, F., Morin, G. (2014) EXAFS analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream of a lateritized ultramafic watershed (Vavouto Bay, New Caledonia). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 136, 211–228.

, 2015Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

), especially in downstream lateritic Ni-ores, where sedimentary pyrite exhibits Ni contents as high as in the present study (1–5 mol. %; Noël et al., 2015Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

).Finally, an enhanced sequestration of Ni in pyrite during early diagenesis of sediments at low temperature could also have influenced the distribution of pyrite and nickel in the ancient sedimentary record. For instance, it may help explain both the exceptionally high Ni contents (up to 1–3 mol. %) found in marine pyrite from the late Archean ocean and the apparent Ni enrichment observed in the core of some of these pyrite grains (Large et al., 2017

Large, R.R., Mukherjee, I., Gregory, D.D., Steadman, J.A., Maslennikov, V.V., Meffre, S. (2017) Ocean and Atmosphere Geochemical Proxies Derived from Trace Elements in Marine Pyrite: Implications for Ore Genesis in Sedimentary Basins. Economic Geology, 112, 423–450.

). Furthermore, it could be inferred that rapid precipitation of Ni-rich pyrite in euxinic basins of the late Archean ocean (Reinhard et al., 2009Reinhard, C.T., Raiswell, R., Scott, C., Anbar, A.D., Lyons, T.W. (2009) A late Archean sulfidic sea stimulated by early oxidative weathering of the continents. Science 326, 713–716.

; Large et al., 2017Large, R.R., Mukherjee, I., Gregory, D.D., Steadman, J.A., Maslennikov, V.V., Meffre, S. (2017) Ocean and Atmosphere Geochemical Proxies Derived from Trace Elements in Marine Pyrite: Implications for Ore Genesis in Sedimentary Basins. Economic Geology, 112, 423–450.

) would be expected to have drastically lowered the Ni/Fe ratio of the ocean, as observed by Konhauser et al. (2009)Konhauser, K.O., Pecoits, E., Lalonde, S.V., Papineau, D., Nisbet, E.G., Barley, M.E., Arndt, N.T., Zahnle, K., Kamber, B.S. (2009) Oceanic nickel depletion and a methanogen famine before the Great Oxidation Event. Nature 458, 750–754.

in BIFs, which could have contributed to trigger the GOE, as proposed by the latter authors.top

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an ANRT- UPMC/CNRS/IRD/IPGP-KNS collaborative research programme. We are greatly indebted to S. Capo (KNS), G. Marakovic (KNS), and C. Marchand (IRD) for the field part of the programme published elsewhere. We acknowledge the help of I. Esteve (CNRS) for SEM, L. Delbes (UPMC) and F. Gélébart (CNRS) for anoxic XRD, L. Cordier (Univ. Paris 7) for ICP-AES, A-L. Auzende (Univ. Genoble-Alpes) for TEM analyses. E. Fonda, V. Briois at SOLEIL, Olivier Mathon at ESRF and M. Munoz (CNRS), are greatly acknowledged for their technical support during EXAFS measurement.

Editor: Simon Redfern

top

References

Berner, R.A. (1970) Sedimentary pyrite formation. American Journal of Science 268, 1–23.

Show in context

Show in context This mineralogical sequence is consistent with pyrite formation pathways at low temperature via a FeS(m) precursor (Berner, 1970; Rickard, 1975; Schoonen and Barnes, 1991).

View in article

Bruno, J., Bosbach, D., Kulik, D., Navrotsky, A. (2007) Chemical thermodynamics of solid solutions of interest in radioactive waste management. A state-of-the-art report. In: Mompean, F.J., Illemassène, M. (Eds.) Chemical Thermodynamics Vol. 10. NEA TDB project, OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, Data Bank, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France.

Show in context

Show in context Assuming saturation equilibrium, the composition of an ideal solid solution Fe1-xNixS2 can be predicted from the solution composition using a theoretical partition coefficient (Bruno et al., 2007): D = KsPy / KsVa = [Feaq]/[Niaq] • x/(1-x) (Tables S-5 and S-6).

View in article

Casey, W.H., Banfield, J.F., Westrich, H.R., McLaughlin, L. (1993) What do dissolution experiments tell us about natural weathering? Chemical Geology 105, 1–15.

Show in context

Show in context Finally, ligand exchange rates of cations correlate well with the reactivity of both divalent metal oxides (Casey et al., 1993) and sulphides (Morse and Luther, 1999) at the solid-water interface.

View in article

Casey et al. (1993) reported that the water exchange rate of the hydrated ion is particularly low for Ni2+ (104.4 s-1) compared to that for Fe2+ (106.5 s-1) and that this difference may explain the lower dissolution rate of Ni-oxides and orthosilicates compared to their Fe analogues.

View in article

Catling, D.C. and Claire, M.W. (2005) How Earth’s atmosphere evolved to an oxic state: A status report. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 237, 1–20.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Darnaud, C., Volbeda, A., Kim, E.J., Legrand, P., Vernède, X., Lindahl, P.A., Fontecilla-Camps, J.C. (2003) Ni-Zn-[Fe4-S4] and Ni-Ni-[Fe4-S4] clusters in closed and open α subunits of acetyl-CoA synthase/carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. Nature Structural Biology 10, 271–279.

Show in context

Show in context In parallel, nickel has been recognised as an essential biocatalytic metal agent in iron-sulphur enzymes, especially acetyl-CoA synthase, which is a major enzyme of acetogenic bacteria and methanogens for fixing CO/CO2 (Darnaud et al., 2003).

View in article

Gamsjäger, H., Bugajski, J., Gajda, T., Lemire, R.J., Preis, W. (2005) Chemical thermodynamics of Nickel. In: Mompean, F.J., Illemassène, M. (Eds.) Chemical Thermodynamics Vol. 6. Nuclear Energy Agency Data Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, North Holland Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Show in context

Show in context This is because the solubility products of pyrite (KsPy = 10-14.2; Rickard and Luther, 2007) and vaesite (KsVa = 10-15.8; Gamsjäger et al., 2005) differ by less than two orders of magnitude (Table S-5).

View in article

Harmandas, N.G., Navarro Fernandez, E., Koutsoukos, P.G. (1998) Crystal Growth of Pyrite in Aqueous Solutions. Inhibition by Organophosphorus Compounds. Langmuir 14, 1250.

Show in context

Show in context Spontaneous pyrite nucleation is generally thought to require a saturation index as large as Log ΩPy* = 14 and/or catalytic effects (Harmandas et al., 1998; Rickard and Luther, 2007).

View in article

Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1997) Acetic Acid by Carbon Fixation on (Fe,Ni)S Under Primordial Conditions. Science 276, 245–247.

Show in context

Show in context Besides, the formation of pyrite from a (Fe,Ni)S precursor has been proposed to be involved in the ‘Fe-S World’ theory of the origin of life (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997, 1998).

View in article

Indeed, when added to a FeS(m) precursor, Ni has been found to facilitate the conversion of CO and CH3SH into the activated thioester CH3–CO–SCH3 (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997), as well as the formation of peptides from amino-acids (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1998).

View in article

Huber, C., Wächtershäuser, G. (1998) Peptides by Activation of Amino Acids with CO on (Ni,Fe)S Surfaces: Implications for the Origin of Life. Science 281, 670–672.

Show in context

Show in context Besides, the formation of pyrite from a (Fe,Ni)S precursor has been proposed to be involved in the ‘Fe-S World’ theory of the origin of life (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997, 1998).

View in article

Indeed, when added to a FeS(m) precursor, Ni has been found to facilitate the conversion of CO and CH3SH into the activated thioester CH3–CO–SCH3 (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1997), as well as the formation of peptides from amino-acids (Huber and Wächtershäuser, 1998).

View in article

Huerta-Diaz, M.A., Morse, J.W. (1992) Pyritization of trace metals in anoxic marine sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 56, 2681–2702.

Show in context

Show in context Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992; Morse and Luther, 1999; Large et al., 2017), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

Johnson, C.M., Beard, B.L., Roden, E.E. (2008) The Iron Isotope Fingerprints of Redox and Biogeochemical Cycling in Modern and Ancient Earth. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science 36, 457–493.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Kitchaev, D.A., Ceder, G. (2016) Evaluating structure selection in the hydrothermal growth of FeS2 pyrite and marcasite. Nature Commmunications 7, 13799.

Show in context

Show in context Slightly lower γ values for pyrite (Kitchaev and Ceder, 2016) than for vaesite (Zheng et al., 2015) would however imply a lower activation energy for the nucleation of pyrite than for vaesite and can thus not be invoked to explain the faster nucleation of Ni-doped pyrite compared to Ni-free pyrite.

View in article

Konhauser, K.O., Pecoits, E., Lalonde, S.V., Papineau, D., Nisbet, E.G., Barley, M.E., Arndt, N.T., Zahnle, K., Kamber, B.S. (2009) Oceanic nickel depletion and a methanogen famine before the Great Oxidation Event. Nature 458, 750–754.

Show in context

Show in context Furthermore, it could be inferred that rapid precipitation of Ni-rich pyrite in euxinic basins of the late Archean ocean (Reinhard et al., 2009; Large et al., 2017) would be expected to have drastically lowered the Ni/Fe ratio of the ocean, as observed by Konhauser et al. (2009) in BIFs, which could have contributed to trigger the GOE, as proposed by the latter authors.

View in article

Large, R.R., Mukherjee, I., Gregory, D.D., Steadman, J.A., Maslennikov, V.V., Meffre, S. (2017) Ocean and Atmosphere Geochemical Proxies Derived from Trace Elements in Marine Pyrite: Implications for Ore Genesis in Sedimentary Basins. Economic Geology, 112, 423–450.

Show in context

Show in context Moreover, trace metals incorporated in pyrite have been recognised as proxies for ancient ocean chemistry (Large et al., 2017).

View in article

Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992; Morse and Luther, 1999; Large et al., 2017), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

For instance, it may help explain both the exceptionally high Ni contents (up to 1–3 mol. %) found in marine pyrite from the late Archean ocean and the apparent Ni enrichment observed in the core of some of these pyrite grains (Large et al., 2017).

View in article

Furthermore, it could be inferred that rapid precipitation of Ni-rich pyrite in euxinic basins of the late Archean ocean (Reinhard et al., 2009; Large et al., 2017) would be expected to have drastically lowered the Ni/Fe ratio of the ocean, as observed by Konhauser et al. (2009) in BIFs, which could have contributed to trigger the GOE, as proposed by the latter authors.

View in article

Lennie, A.R., Redfern, S.A.T., Schofield, P.F., Vaughan, D.J. (1995) Synthesis and Rietveld crystal structure refinement of mackinawite. Mineralogical Magazine 59, 677–683.

Show in context

Show in context The first solid phase that formed in our pyrite synthesis experiments was nanocrystalline mackinawite, FeS(m) (Lennie et al., 1995; Rickard and Luther, 2007), rapidly followed by the crystallisation of minor amounts of S(0)(alpha) (Fig. 1).

View in article

Luther, G.W. (1991) Pyrite synthesis via polysulfide compounds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 55, 2839–2849.

Show in context

Show in context According to Rickard (1975), this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975; Luther, 1991; Theberge and Luther, 1997; Rickard and Morse 2005; Rickard and Luther 2007), e.g., for p = 1: FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

View in article

Marin-Carbonne, J., Rollion-Bard, C., Bekker, A., Rouxel, O., Agangi, A., Cavalazzi, B., Wohlgemuth-Ueberwasser, C.C., Hofmann, A., McKeegan, K.D. (2014) Coupled Fe and S isotope variations in pyrite nodules from Archean shale. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 392, 67–79.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Morse, J.W., Luther III, G.W. (1999) Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 63, 3373–3378.

Show in context

Show in context Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992; Morse and Luther, 1999; Large et al., 2017), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

Conversely, the possible effects of metal impurities such as nickel on the formation of pyrite have not been investigated yet, especially at low-temperature (Morse and Luther, 1999; Rickard and Luther, 2007).

View in article

Finally, ligand exchange rates of cations correlate well with the reactivity of both divalent metal oxides (Casey et al., 1993) and sulphides (Morse and Luther, 1999) at the solid-water interface.

View in article

In addition, Morse and Luther (1999) proposed that, since Ni2+ has lower kinetics of water exchange than Fe2+, incorporation of Ni2+ into FeS2 should be kinetically favoured over precipitation of pure NiS2, as we demonstrate here.

View in article

Noël, V., Marchand, C., Juillot, F., Ona-Nguema, G., Viollier, E., Marakovic, G., Olivi, L., Delbes, L., Gelebart, F., Morin, G. (2014) EXAFS analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream of a lateritized ultramafic watershed (Vavouto Bay, New Caledonia). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 136, 211–228.

Show in context

Show in context Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992; Morse and Luther, 1999; Large et al., 2017), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

Pyrite (FeS2) was synthesised by reacting ferric chloride with sodium sulphide in aqueous solution for two weeks at room temperature under strict anoxic conditions (Noël et al., 2014, 2015), with or without nickel chloride as impurity (Ni/Fe = 0.01 mol/mol) in the starting solution (∑Fe(III) + Ni(II) = ∑S(-II) = 50 mM at pH 5.5; Table S-1).

View in article

EXAFS spectra of the solids collected over the course of the experiments were analysed by linear combination least squares (LC-LS) fitting using a large model compounds spectra database (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

For instance, fast incorporation of Ni in pyrite could explain the efficiency of this trapping process in mangrove sediments (Noël et al., 2014, 2015), especially in downstream lateritic Ni-ores, where sedimentary pyrite exhibits Ni contents as high as in the present study (1–5 mol. %; Noël et al., 2015).

View in article

Noël, V., Morin, G., Juillot, F., Marchand, C., Brest, J., Bargar, J.R., Muñoz, M., Marakovic, G., Ardo, S., Brown Jr., G.E. (2015) Ni cycling in mangrove sediments from New Caledonia. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 169, 82–98.

Show in context

Show in context Lastly, nickel has a particular ability to be incorporated in pyrite during early diagenesis of marine and coastal sediments (Huerta-Diaz and Morse, 1992; Morse and Luther, 1999; Large et al., 2017), which largely contributes to Ni immobilisation in mangroves (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

Pyrite (FeS2) was synthesised by reacting ferric chloride with sodium sulphide in aqueous solution for two weeks at room temperature under strict anoxic conditions (Noël et al., 2014, 2015), with or without nickel chloride as impurity (Ni/Fe = 0.01 mol/mol) in the starting solution (∑Fe(III) + Ni(II) = ∑S(-II) = 50 mM at pH 5.5; Table S-1).

View in article

EXAFS spectra of the solids collected over the course of the experiments were analysed by linear combination least squares (LC-LS) fitting using a large model compounds spectra database (Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

View in article

For instance, fast incorporation of Ni in pyrite could explain the efficiency of this trapping process in mangrove sediments (Noël et al., 2014, 2015), especially in downstream lateritic Ni-ores, where sedimentary pyrite exhibits Ni contents as high as in the present study (1–5 mol. %; Noël et al., 2015).

View in article

Ohmoto, H., Watanabe, Y., Ikemi, H., Poulson, S.R., Taylor B.E. (2006) Sulphur isotope evidence for an oxic Archaean atmosphere. Nature Letter 442, 908–911.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Reinhard, C.T., Raiswell, R., Scott, C., Anbar, A.D., Lyons, T.W. (2009) A late Archean sulfidic sea stimulated by early oxidative weathering of the continents. Science 326, 713–716.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Furthermore, it could be inferred that rapid precipitation of Ni-rich pyrite in euxinic basins of the late Archean ocean (Reinhard et al., 2009; Large et al., 2017) would be expected to have drastically lowered the Ni/Fe ratio of the ocean, as observed by Konhauser et al. (2009) in BIFs, which could have contributed to trigger the GOE, as proposed by the latter authors.

View in article

Rickard, D.T. (1975) Kinetics and mechanism of pyrite formation at low-temperature. American Journal of Science 275, 636–652.

Show in context

Show in context This mineralogical sequence is consistent with pyrite formation pathways at low temperature via a FeS(m) precursor (Berner, 1970; Rickard, 1975; Schoonen and Barnes, 1991).

View in article

According to Rickard (1975), this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975; Luther, 1991; Theberge and Luther, 1997; Rickard and Morse 2005; Rickard and Luther 2007), e.g., for p = 1: FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

View in article

Rickard, D.T., Morse J. (2005) Acid volatile sulfide (AVS) Marine Chemistry 97, 141.

Show in context

Show in context According to Rickard (1975), this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975; Luther, 1991; Theberge and Luther, 1997; Rickard and Morse 2005; Rickard and Luther 2007), e.g., for p = 1: FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

View in article

Rickard, D.T., Luther, G.W. (2007) Chemistry of Iron Sulfides. Chemical Reviews 107, 514−562.

Show in context

Show in context Conversely, the possible effects of metal impurities such as nickel on the formation of pyrite have not been investigated yet, especially at low-temperature (Morse and Luther, 1999; Rickard and Luther, 2007).

View in article

The first solid phase that formed in our pyrite synthesis experiments was nanocrystalline mackinawite, FeS(m) (Lennie et al., 1995; Rickard and Luther, 2007), rapidly followed by the crystallisation of minor amounts of S(0)(alpha) (Fig. 1).

View in article

According to Rickard (1975), this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975; Luther, 1991; Theberge and Luther, 1997; Rickard and Morse 2005; Rickard and Luther 2007), e.g., for p = 1: FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

View in article

Spontaneous pyrite nucleation is generally thought to require a saturation index as large as Log ΩPy* = 14 and/or catalytic effects (Harmandas et al., 1998; Rickard and Luther, 2007).

View in article

This is because the solubility products of pyrite (KsPy = 10-14.2; Rickard and Luther, 2007) and vaesite (KsVa = 10-15.8; Gamsjäger et al., 2005) differ by less than two orders of magnitude (Table S-5).

View in article

Rouxel, O.J., Bekker, A., Edwards, J. (2005) Iron Isotope Constraints on the Archean and Paleoproterozoic Ocean Redox State. Science 307, 1088–1091.

Show in context

Show in context Pyrite is widely used as a geochemical marker in sediments from the Archean to modern eras. Isotopic compositions of iron and sulphur in pyrites from sedimentary rocks have been proposed as potential proxies to assess the redox state of ancient oceans (Rouxel et al., 2005; Reinhard et al., 2009; Marin-Carbonne et al., 2014), the oxygen outgrowth in the atmosphere (Catling and Claire, 2005; Ohmoto et al., 2006) and early microbial metabolisms (Johnson et al., 2008).

View in article

Schoonen, M.A.A., Barnes, H.L. (1991) Reactions forming pyrite and marcasite fom solution 2. Via FeS precursors below 100°C. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 55, 1505–1514.

Show in context

Show in context This mineralogical sequence is consistent with pyrite formation pathways at low temperature via a FeS(m) precursor (Berner, 1970; Rickard, 1975; Schoonen and Barnes, 1991).

View in article

Stumm, W. (1992) Chemistry of the solid-water interface. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Show in context

Show in context Interfacial energy γ is known to influence the rate of nucleation from solution (Stumm, 1992).

View in article

Theberge, S., Luther, G.W. (1997) Determination of the electrochemical properties of a soluble aqueous FeS species present in sulfide solutions. Aquatic Geochemistry 3, 191–211.

Show in context

Show in context According to Rickard (1975), this conversion actually proceeds via the reaction between aqueous polysulphide ions Sn2-(aq) in equilibrium with S(0), and aqueous [FeS]p(aq) oligomers in equilibrium with FeS(m) (Rickard, 1975; Luther, 1991; Theberge and Luther, 1997; Rickard and Morse 2005; Rickard and Luther 2007), e.g., for p = 1: FeS(aq) + H2Sn(aq) ⇆ FeS2(pyrite) + H2Sn-1(aq)

View in article

van der Lee, J., De Windt, L. (2002) CHESS Tutorial and Cookbook. Updated for version 3.0. Users Manual Nr. LHM/RD/02/13. Ecole des Mines de Paris, Fontainebleau, France.

Show in context

Show in context Based on these values that remained almost constant during the 24-29 hours lag phase (Fig. 4b), with a slight decrease for Ni (Table S-6), Chess 3.0 (van der Lee and De Windt, 2002) calculations show that the saturation index of any ideal pyrite-vaesite solid solutions was in between the saturation indexes of the FeS2(pyrite) and NiS2(vaesite) end members (i.e. Log ΩPy = 12.3 and Log ΩVa = 9.9, respectively).

View in article

Wyckoff, R.W.G. (1963) Crystal Structures. Second Edition, Volumes 1–6. Interscience, New York.

Show in context

Show in context Fe K-edge EXAFS spectra of the Ni-free (Fig. S-2 and Table S-3) and of the Ni-doped end products (Fig. 2b and Table S-3) well matched pyrite crystallographic data (Wyckoff, 1963).

View in article

Zheng, J., Zhou, W., Ma, Y., Cao, W., Wang, C., Guo, L. (2015) Facet-dependent NiS2 polyhedrons on counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chemical Communications 51, 12863.

Show in context

Show in context Slightly lower γ values for pyrite (Kitchaev and Ceder, 2016) than for vaesite (Zheng et al., 2015) would however imply a lower activation energy for the nucleation of pyrite than for vaesite and can thus not be invoked to explain the faster nucleation of Ni-doped pyrite compared to Ni-free pyrite.

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

1. Pyrite Synthesis Procedure

Pyrite (FeS2) was synthesised at room temperature following the protocol of Noël et al. (2014, 2015) with or without dissolved Ni2+ as impurity in the starting solution. All experiments were conducted under strict anoxia using glass vials sealed by butyl rubber stoppers in a glove box, and using O2-free Milli-Q water degassed via N2 bubbling for 45 min at 80 °C. The pyrite synthesis was performed over 2 weeks of reaction at pH 5.2–5.8, in 50 mL total volume with starting concentrations of 50 mM FeCl3 and 50 mM Na2S. The experiment with Ni2+ as impurity was conducted with 0.5 mM NiCl2, 49.5 mM FeCl3 and 50 mM Na2S in the starting solution (Table S-1). Over the course of pyrite formation, aliquots of 3 mL were regularly collected from the reacting suspensions. The solid phase was harvested by centrifugation at 8,500 g for 10 min, rinsed three times with O2-free Milli-Q water, and dried under vacuum within the anaerobic glove box. The aqueous phase was collected after centrifugation, filtered through 0.22 μm cellulose filters, and stored under anoxic conditions at 4 °C, until analysis.

Table S-1 Proportions of the reactants used for the two pyrite synthesis experiments performed without or with aqueous Ni2+ impurity in the starting solution. All solutions were prepared with O2-free milli-Q water in an anaerobic chamber. Appropriate volumes (v) of metal cation stock solutions of concentrations (c) were mixed with 42 mL of O2-free milli-Q water under stirring and completed with 4 mL of Na2S solution to 50 mL total volume (VTotal) in glass vials. These vials with initial concentrations of the reactants (C) were then sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and reacted for two weeks at 25 °C under constant strirring. Solution pH at the start and end of the synthesis experiments are also reported.

| c | v | n | C | pH | |

| (M) | (mL) | (mmol) | (mM) | ||

| without Ni | |||||

| O2-free mQ water | 42 | ||||

| FeCl3•6H2O | 0.625 | 4 | 2.5 | 50 | |

| Na2S•9H2O | 0.625 | 4 | 0.4 | 50 | |

| VTotal | 50 | ||||

| pH start | 5.8 | ||||

| pH end | 5.2 | ||||

| with Ni | |||||

| O2-free mQ water | 41.79 | ||||

| NiCl2•6H2O | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.025 | 0.5 | |

| FeCl3•6H2O | 0.625 | 3.96 | 2.475 | 49.5 | |

| Na2S•9H2O | 0.625 | 4 | 0.4 | 50 | |

| VTotal | 50 | ||||

| pH start | 5.7 | ||||

| pH end | 5.8 | ||||

2. Aqueous Phase Analyses

Dissolved metal concentrations in the aqueous phase were measured after 100 times dilution, by ICP-AES (Icap ThermoFisher Scientific at University Paris Diderot) for Fe and HR-ICP-MS with an integrated FAST (ESI) injection system (Element 2 Thermofisher Scientific at University Paris Diderot) for Ni. Certified reference materials (SLRS4) were intercalated during the analytical series.

3. Powder X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Mineralogical composition of the solid samples collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments was determined by powder XRD, using CoKα radiation in order to minimise the X-ray absorption of Fe. Data were collected in Bragg-Brentano geometry using a Panalytical® X’Pert Pro diffractometer equipped with an X’celerator® detector. A continuous collection mode was applied over the 3–80° 2θ range with a 0.016° 2θ step and counting 3 hr for each sample. To avoid any changes in the mineralogy related to possible redox reaction with air during this analysis, samples were mounted on a XRD sample holder that was loaded in a sealed chamber equipped with a Kapton window for XRD analysis. All these operations were done within a glove box filled with nitrogen.

4. Wide-angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS) and Pair Distribution Function (PDF) Analysis

The solid phases sampled at 0.5 hr and 216 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment, and respectively identified as nano-mackinawite and pyrite using XRD (Fig. 1), were analysed by WAXS-PDF analysis in order to better determine their local structure. Total X-ray scattering data were collected at IMPMC using a Panalytical Empyrean diffractometer equipped with an Ag anode and a photo-multiplier detector, in a θ – θ transmission geometry, on samples loaded in borosilicate capillaries. Measurements were performed up to 2θ = 148° with Ag Kα radiation (Kα1 0,559421 Å, Kα2 0,563812 or 22.16 keV) allowing the collection of data up to Qmax = 21.8 Å-1, where Q is the magnitude of the scattering vector, Q = (4πsinθ)/λ). To minimise the statistical noise level at high Q values (due to the low form factor at high angle), the exposure time used for 2° < 2θ < 50° (10 s per 0.2° step) was doubled for 50° < 2θ < 90° and quadrupled for 90° < 2θ < 148°. The same data collection strategy was used for both the samples and empty borosilicate capillary, the latter being used as a baseline that was subtracted from sample data.

The PDF G(r) gives the probability of finding a pair of atoms separated by a distance r. It is experimentally obtained from the sine Fourier transform of the scattering function S(Q) (Egami and Billinge, 2003; Farrow and Billinge, 2009) as shown in the following equation:

The agreement between the calculated and the experimental PDF was characterised by the following reliability factor:

is the list of parameters refined in the model.

is the list of parameters refined in the model.

Figure S-1 PDF analysis of the samples collected at 0.5 hr and 216 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment. For the 0.5 hr and 216 hr samples, the best fits were obtained from the refinement in real space of the mackinawite structure (Lennie et al., 1995) and the pyrite structure (Wyckoff et al., 1963) respectively (Table S-2). Experimental and calculated PDF curves are plotted in black and red colours, respectively.

Table S-2 Refined crystallographic parameters obtained from the PDF analysis of the samples collected at 0.5 hr and 216 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment, using the mackinawite (Lennie et al., 1995) and pyrite (Wyckoff et al., 1963) structures as starting models, respectively.

| Mackinawite (0.5 hr) | unit-cell (P4/nmm) | atomic positions | MCD | Rw | ||||

| a,b | c | atom | x | y | z | (nm) | ||

| Staring parameters | 3.6735 | 5.0328 | Fe | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| S | 0 | 0.5 | 0.2602 | |||||

| Refined parameters | 3.674(1) | 5.033(1) | Fe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.1(3) | 0.45 |

| S | 0 | 0.5 | 0.27(3) | |||||

| Pyrite (216 hr) | unit-cell (Pa3) | atomic positions | MCD | Rw | ||||

| a,b,c | atom | x | y | z | (nm) | |||

| Staring parameters | 5.4067 | Fe | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S | 0.386 | 0.386 | 0.386 | |||||

| Refined parameters | 5.448(4) | Fe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.9(6) | 0.38 | |

| S | 0.385(1) | 0.385(1) | 0.385(1) | |||||

5. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM)

Data were collected on a JEOL 2100F microscope (IMPMC, Paris) operating at 200 kV, equipped with a field emission gun, a high-resolution (UHR) pole piece and a Gatan energy filter GIF 2001. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) in high angle annular dark field (HAADF) allowed Z-contrast imaging. Qualitative elemental compositions were determined by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) using a JEOL detector with an ultra-thin window allowing detection of light elements.

6. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Data Collection

Fe and Ni K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of the solid phases were collected in transmission detection mode at 20 oK on the bending magnet beamlines SAMBA (SOLEIL, Saint-Aubin, France) and BM23 (ESRF, Grenoble, France) using a Si(220) or a Si(111) double-crystal monochromator, respectively. Dynamic sagittal focusing of the second crystal was used at the SAMBA beamline (Briois et al., 2011). In order to strictly preserve the oxidation state of Fe during the analyses, all samples were mounted on the cryostat sample rod within a glove bag or a glove box next to the beamline and carried to the beamline in a liquid nitrogen bath before being rapidly transferred into the cryostat. The energy of the X-ray beam was calibrated by setting to 7112 eV (or 8333 eV) the first inflection point on the Fe (or Ni) K-edge spectrum recorded on a Fe foil (or a Ni foil) in double transmission setup. Only 2 scans were needed for Fe K-edge spectra, whereas 3 to 4 scans were needed to achieve an acceptable signal/noise ratio for Ni K-edge spectra. For each sample, data were averaged and normalised using the ATHENA software (Ravel and Newville, 2005). EXAFS spectra were then background subtracted from these normalised data using the XAFS code (Winterer, 1997). Radial distribution functions around the Fe (or Ni) absorber were obtained by Fast Fourier-transformation of the k3-weighted experimental χ(k) function using a Kaiser-Bessel apodisation window with the Bessel weight set at 2.5.

7. Ab Initio Calculation of the EXAFS Spectra

The local structure around Fe and Ni atoms in the pyrite end products synthesised with and without aqueous Ni was analysed by comparison of the experimental EXAFS spectra of these samples at the Fe and Ni K-edges with theoretical spectra calculated using the Feff8.1 code. For that purpose, atomic clusters around central Fe or Ni atom were generated using the Atoms code (Ravel, 2001) on the basis of the pyrite crystal structure (Wyckoff, 1963). When the Ni atom was considered as the central atom, the cell parameter of the pyrite cluster was modified to account for the difference in unit cell between pyrite (FeS2) and vaesite (NiS2) (5.4067 and 5.677 Å, respectively; Wyckoff, 1963). The unit cell parameter was increased to a = 5.52 Å for the first shell around the central Ni atom and to a = 5.45 Å for longer distances (Table S-3). This is in agreement with previous EXAFS results that showed shorter Ni-S distances in Ni-substituted pyrite than in vaesite (Noël et al., 2015). For each cluster, a few hundred theoretical phase shift and amplitude functions were calculated using the FEff8.1 code (Ankudinov et al., 1998), over a radius of 8 Å, including multiple scattering paths up to nleg = 6 with criteria = 1.5. For these calculations, the self-consistent potential option of the FEff8.1 code was not used. Each theoretical EXAFS spectrum reconstructed using all these path functions was then least squares fitted to the experimental EXAFS spectrum of the chosen model compound using a custom-built software based on a Levenberg-Marquardt minimisation algorithm, refining only an overall Debye-Waller parameter σ and a threshold energy shift ∆E0 parameter, with S02 fixed to 1. The fit quality was estimated using a Rf value. Uncertainty on each refined parameter was estimated as

, where VAR(p) is the variance of parameter p returned by the Levenberg–Marquardt routine for the lowest Rf. Results of these calculations are reported in Table S-3. Corresponding spectra are plotted in Figures 2a,b, S-2, and Figure 2c,d for Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data, respectively.

, where VAR(p) is the variance of parameter p returned by the Levenberg–Marquardt routine for the lowest Rf. Results of these calculations are reported in Table S-3. Corresponding spectra are plotted in Figures 2a,b, S-2, and Figure 2c,d for Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data, respectively.Table S-3 Crystallographic data used for ab initio Feff8.1 calculations of Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data for the synthetic Ni-free and Ni-doped pyrite end products. Corresponding k3χ(k) EXAFS and FFT curves are plotted in Figure S-2 as well as in Figure 2a,b and in Figure 2c,d, for the Fe and Ni K-edge data, respectively. Interatomic distances between the central Fe or Ni atom and its closest neighbours in the cluster are reported. To adjust the amplitude and the energy position of the EXAFS spectra, an overall Debye-Waller parameter σ and a threshold energy shift ∆E0 parameter were simultaneously refined. The S02 parameter was fixed to 1. Fit quality was estimated using an R-factor (Rf) and uncertainty on the refined parameters are given in parentheses (see text).

| Sample | Unit-cell | closest neighbors | Refined parameters | ||||

| a(Å) | atom | R(Å) | N | σ (Å) | ∆E0 (eV) | Rf | |

| Fe K-edge | |||||||

| Ni-free pyrite (336 hr) | 5.407 | S | 2.26 | 6 | 0.070(4) | 2.1(5) | 0.16 |

| S | 3.43 | 6 | |||||

| S | 3.61 | 2 | |||||

| Fe | 3.82 | 12 | |||||

| S | 4.44 | 6 | |||||

| Ni-doped pyrite (44 hr) | 5.407 | S | 2.26 | 6 | 0.071(4) | 2.2(5) | 0.10 |

| S | 3.43 | 6 | |||||

| 3.61 | 2 | ||||||

| Fe | 3.82 | 12 | |||||

| S | 4.44 | 6 | |||||

| Ni K-edge | |||||||

| Ni-doped pyrite (44 hr) | 5.52 | S | 2.31 | 6 | 0.071(4) | 2.2(5) | 0.08 |

| 5.45 | S | 3.46 | 6 | ||||

| S | 3.64 | 2 | |||||

| Fe | 3.85 | 12 | |||||

| S | 4.48 | 6 | |||||

8. Linear Combination Least Squares (LC-LS) Fitting of the Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS Data

Fe and Ni-EXAFS of the solids sampled over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments were fit with a Linear Combination Least Squares (LC-LS) procedure using a custom-built software based on the Levenberg-Marquardt minimisation algorithm. This procedure relied on a large set of experimental Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS spectra from natural and synthetic sulphide model compounds (Dublet et al., 2012; Noël et al., 2014, 2015).

The model compound spectra that gave the best LC-LS fits to the Fe K-edge spectra (Figs. 2, S-2 and Table S-3) were the following: i) the nano-mackinawite sampled after 0.5 hr in the Ni-free synthesis experiment (local structure determined by WAXS-PDF analysis; Table S-2 and Fig. S-1); ii) the pyrite end product of the Ni-free synthesis experiment identified by XRD (Fig. 1a) (i.e. structure determined by WAXS-PDF analysis; Table S-2 and Fig. S-1, and ab initio Feff8.1 EXAFS calculation; Fig. S-2 and Table S-3); iii) the Ni-doped pyrite end product characterised by XRD (Fig. 1b) and EXAFS (i.e. local structure determined by ab initio Feff8 calculation; Fig. S-2 and Table S-3).

For Ni K-edge, the best model compounds were the following: i) Ni-subsituted mackinawite, the local structure determined by ab initio Feff8 calculation (Noël et al., 2015); ii) amorphous NiS (see Fig. S-5 in Noël et al., 2015); and iii) the Ni-doped pyrite end product characterised XRD (Fig. 1b) and EXAFS (i.e. structure determined by ab initio Feff8 calculation; Fig. 2 and Table S-3).

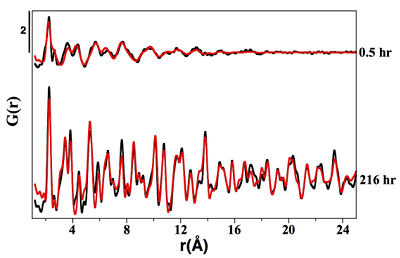

Goodness of fit was estimated by a reduced chi-squares

, where Nind = (2∆k∆R)/π) is the number of independent parameters, Np is the number of fitting components, Npoints the number of data points and ε is the measurement uncertainty (Noël et al., 2015). The ε value was estimated as the root mean square of the Fourier back-transform of the data in the 15-25 Å R-range (Ravel et al., 2005). Uncertainty on each fitting parameter p was estimated as

, where Nind = (2∆k∆R)/π) is the number of independent parameters, Np is the number of fitting components, Npoints the number of data points and ε is the measurement uncertainty (Noël et al., 2015). The ε value was estimated as the root mean square of the Fourier back-transform of the data in the 15-25 Å R-range (Ravel et al., 2005). Uncertainty on each fitting parameter p was estimated as  , where VAR(p) is the variance of parameter p returned by the Levenberg–Marquardt routine for the lowest Χ2R.

, where VAR(p) is the variance of parameter p returned by the Levenberg–Marquardt routine for the lowest Χ2R.

Figure S-2 Fe K-edge k3-weighted EXAFS data of the solid samples collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted without aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Experimental k3χ(k) functions (left panel) and corresponding Fast Fourier Transforms (centre panel) are displayed as black lines. Ab initio calculation of the EXAFS spectra of the pyrite end product is displayed in purple (Table S-3). Linear combination least squares (LC-LS) fits of the solid samples collected over the course of the synthesis experiments are displayed in gray curves. Proportions of the LC-LS fitting components (right panel) are reported in Table S-4.

Table S-4 Results of LC-LS fits for Fe and Ni K-edge EXAFS data of the solids collected over the course of the pyrite synthesis experiments conducted with (Fig. 2) or without (Fig. S-2) aqueous Ni in the starting solution. Results are given in percentage of the following fitting components: the nanocrystalline mackinawite (nano-mack) collected at 0.5 hr in the Ni-free experiment; the pyrite end product of the Ni-free experiment (pyrite), the Ni-doped pyrite end product of the experiment conducted with Ni (Ni-doped pyrite), amorphous NiS (am-NiS), nanocrystalline Ni-doped mackinawite (Ni-Mack). Using vaesite NiS2 as fitting component did not match the data. Uncertainties on the component proportions are given in brackets for the last digit. Goodness of fit is evaluated by a reduced χ2R (see SI text).

| Sample | pyrite | nano-mack | Ni-doped pyrite | am-NiS | Ni-mack | Sum | χ2R |

| without Ni | |||||||

| Fe K-edge | |||||||

| 0.5 hr | - | 100 | 100 | 0 | |||

| 84 hr | 4(2) | 100(3) | 104 | 1 | |||

| 120 hr | 18(14) | 82(23) | 100 | 12 | |||

| 216 hr | 100 | - | 100 | 0 | |||

| with Ni impurity | |||||||

| Fe K-edge | |||||||

| 15 hr | 100 | 3(7) | 103 | 7.6 | |||

| 24 hr | 90(14) | 16(9) | 106 | 3.9 | |||

| 29 hr | 83(9) | 19(6) | 102 | 1.5 | |||

| 44 hr | - | 100 | 100 | 0 | |||

| Ni K-edge | |||||||

| 0.5 hr | - | 90(13) | 27(6) | 117 | 3.2 | ||

| 29 hr | 57(3) | 46(6) | 9(3) | 112 | 0.5 | ||

| 30 hr | 70(3) | 27(7) | 5(3) | 102 | 0.9 | ||

| 48 hr | 100 | - | - | 100 | 0 |

9. Aqueous Chemistry Calculations

Saturation indexes of the Ni and Fe sulphide mineral phases were calculated using the Chess 3.0 code, release 4, compiled March 6th 2003 for MacOSX, and using the Chess code database (Van der Lee, 2002), completed by the specific thermodynamic data listed in Table S-5. Saturation equilibrium calculations (Table S-6) were performed according to the formalism by Bruno et al. (2007) and using the thermodynamic data listed in Table S-5.

For our starting chemical compositions (∑Fe(III) + Ni(II) = ∑S(-II) = 50 mM at pH 5.5; Table S-1), Chess 3.0 calculation indicates that the saturation index of FeS2(pyrite) (Log ΩPy = 15.7) exceeded the supersaturation limit (Log ΩPy* = 14; Harmandas et al., 1998; Rickard and Luther, 2007) at which pyrite nucleation is relatively fast and not rate limiting. However, in all synthesis experiments conducted with or without Ni2+, nanocrystalline mackinawite formed first (Fig. 1), indicating that it was kinetically favoured over pyrite, although the starting chemical composition was moderately supersaturated with respect to nanocrystalline mackinawite FeS(m) (Log ΩFeS(m) = 4.3), as calculated with Chess 3.0 using thermodynamic data from Table S-5. Within the first 30 minutes of synthesis conducted in the absence of Ni, the precipitation of FeS(m) in the absence of S(0)(alpha)[1] resulted in a decrease of aqueous sulphide and iron concentrations down to the same value of 28 mM as measured by ICP-AES for Fe (Fig. 4b). Based on these measured concentrations, the saturation index with respect to FeS2(pyrite) was then estimated from Chess 3.0 calculation to have decreased to Log ΩPy = 12.3.

In the same way, in the experiment with Ni, nanocrystalline mackinawite and amorphous NiS formed first (Fig. 2), although the starting chemical composition was moderately supersaturated with respect to FeS(m) (Log ΩFeS(m) = 4.3) and NiS(ppt) (Log ΩNiS(ppt) = 4.4), as calculated with Chess 3.0 using thermodynamic data from Table S-5. The precipitation of FeS(m) and amorphous NiS, in the absence of S(0)(alpha), during the first 30 min of synthesis resulted in a decrease of aqueous sulphide and iron concentrations down to 28 mM, and of aqueous nickel concentration down to 57 µM. Based on these measured concentration values, saturation indexes with respect to pyrite-vaesite solutions were estimated with Chess 3.0 code (see text). For these calculations, the solubility products Ks,x of Fe1-xNixS2 solid solutions were estimated assuming ideal mixing using a formalism adapted from Bruno et al. (2007) (i.e. Log Ks,x = (1-x)Log[(1-x)KsPy] + xLog [xKsVa], where KsPy and KsVa are the solubility products of FeS2(pyrite) and NiS2(vaesite), respectively; Table S-5).

[1]At this stage, sulphide aqueous species likely include polysulphide ions such as e.g., H2S2(aq), resulting from Fe(III) reduction by S(-II) :

Fe(OH)2+(aq) + H2S(aq) + H+(aq) ⇆ Fe2+(aq) + ½ H2S2(aq) + 2 H2O(I)

Table S-5 Solubility data for relevant Fe and Ni sulphide solid phases and aqueous species used in the aqueous chemistry calculation displayed in Figure 4. Dissolution reactions are written in terms of HS-, SO42-, S(0), Fe2+ and Ni2+ for consistency with the Chess code database. The equilibrium constants of these reactions have been converted from reported reactions and constants given below.

| Log K | ∆fG0m | |||

| Reactions converted into the Chess database framework | (kJ.mol-1) | |||

| 1 | FeS(m) + H+(aq) = Fe2+(aq) + HS-(aq) | -3.5 | Rickard (2006) | |

| 2 | NiS(ppt) + H+(aq) = Ni2+(aq) + HS- (aq) | -7.5 | Gamsjäger et al. (2005) | |

| 3 | FeS2(pyrite) + H2O(l) = Fe2+(aq) + 1.75 HS-(aq) + 0.25 SO42-(aq) + 0.25 H+(aq) | -24.7 | from 8, 10, 11 | |